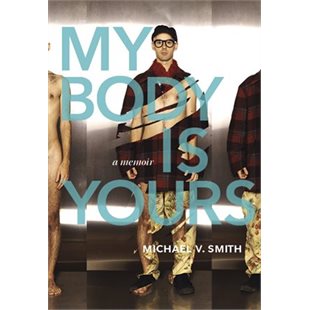

Michael V. Smith by rights should have reporters outside his door daily (see his answer to question seven below). He is fully himself, shameless in the best way, thoughtful and delightful to talk with. He's the author of several books, including the novels Progress (2011) and Cumberland (2002), which was nominated for the Amazon.ca First Novel Award. He's also a poet, filmmaker, reviewer, beloved performer, buster of gender norms, and, as he puts it, "occasional clown." I'm so glad to have gotten to know Michael in person over the last few months, as I've liked his work since reading his Journey Prize-nominated story "What We Wanted" years ago. It's about a young queer boy who feels responsible for a horrible accident. Michael's new memoir, My Body is Yours, also gets under the skin of a boy, this time himself, as he grows up, and once he's a man trying to come to terms with compulsion and pain, his own gayness and his father's last illness. It's a hell of a read, intense and insightful and redemptive. I admire writers who can pull off memoir without flinching or self-pity or sinking into what Twain called "dollar-book Freud," and there's none of that here. I admire this book tremendously, and I'd hope to create a first-person voice for my fictional Dan that's as strong as this one. Here's what Michael said about his writing process. 1. Did you have any alternate titles for the book? What made you pick My Body is Yours? We’d started with a bunch of titles in mind, and nearly went with “Your Heart is Hungry Too,” but that just sounded too cheesy and obvious. I wanted something with more complexity. And, really, my father was dead by then, and he’s a big part of the book, so that title didn’t suggest anything about him. My Body Is Yours was the title of a retrospective film screening I had in Berlin in 2011. It featured a bunch of my short films, in which I mostly used my body as a tool for discussing larger issues of gender, addiction, and sexuality, obviously. That title worked for this book—it’s a little pervy, it’s overly intimate—but it also speaks about my father, and the notion of his biological legacy. I wanted something that could address multiple topics. There’s a complex conversation happening in the memoir, so we wanted a title that could match it. 2. How did you decide on the structure for this book--a set of connecting pieces about your life? The book really grew out of an essay I wrote for a great Arsenal Pulp Press anthology, Persistence: All Ways Butch and Femme. Brian Lam approached me at the launch and suggested we could do a nonfiction book together. That essay, “A Failed Man,” was the core of this book. We agreed that I’d write a book about gender and masculinity, but I’d pitched something with a stronger cultural bent. I wasn’t writing a memoir—I was making a cultural critique, a set of essays on how I saw masculinity manifest in the world I knew. But like all books, this one had its own story, its own trajectory, and it became my job to listen to it, and to follow. So the structure of the memoir really determined itself. 3. In spite of being episodic, the book has a clear shape. Did you know from the start how you were going to finish? Did the ending remain the same through different drafts? I put the book together in pieces. I used a few more essays I’d previously written, and expanded them greatly. I wrote a bunch of new things, I read a lot of books, and the personal story won out over and over again. The intimate stuff was simply more compelling. I couldn’t get the same depth of insight or care in the general as I could in the specifics of my own experience. And by the end of the writing process, the story about my father’s decline and the climax of my addiction declared itself loud and clear. With the end of a manuscript, you figure out what you were writing about all along. And the shape of the book, then, settles. 4. Could you choose a piece of music to go with this book? Now nobody has asked me that question before. I’ll pick the album Crane Wars, by Beans*, a defunct Vancouver band who did a lot of great things, like concerts with visuals that made a sort of live filmic experience. They were orchestral in scope, like Godspeed You Black Emperor. Brilliant, fun, engaging, and deeply intimate works. My memoir aspires to the breadth and beauty of that band. 5. The book talks about creating your performing alter ego, Cookie, and about welding your other self to that one. In writing, especially the very honest and revealing sections about your life and mind, did you find you had to take on that performing persona? Can you talk about that? I don’t think the book was taking on a persona. I know that narrators are a construction—I teach my students that all the time, that we pick and choose, and in those choices cobble a narrator together—but this narrator wasn’t about adopting a persona. Rather, it was made with listening. Listening better. I felt like I was finding a truer voice than the one I use in day-to-day life, because I could release a clear-eyed, candid me. The me that would have a conversation with myself. You can say things in books you might never have permission to say in the real world—whether that’s a permission others do or don’t give you, or a permission you refuse to give yourself. The job I gave myself for My Body Is Yours was to listen well to that personal confession and insight, to listen to the uncomfortable stuff, to ask that place of discomfort some hard questions, and to feel safe enough to hear the answers. The writer then had to put those answers in some context. I translated those responses as best I could for a reading public. So the narrative project wasn’t to adopt a persona like Cookie, who gave me so much permission in public to say the naughty thing, to be playful and dangerous and truthful, but to find a deeper sense of self, and give voice to that. To approach another side of this question, though, I’d add that what Cookie and this narrator share, I think, is a bravado that comes from conviction. 6. This book is about constructing (and deconstructing) yourself as a man, but also about how your father constructed himself. I'm interested in your view of the layers here--a writer building a picture of another person, one who was quite closed off in some ways. Did you find this hard? The book is a kind of apology to my father, I guess. It’s trying to make space in the world so that people like my father—who suffer greatly for being failed men, men who are expected to live up to a standard they can’t meet—might find the world more forgiving. It’s a compassionate book. Compassion for my dad and compassion for me. I wrote the book to have a conversation about the massive gap I experienced between my life as a man and the cultural fabric of masculinity—what I felt and what was expected of me. The gap between what my father felt he had permission to do and what I wanted for him. And from him. Much of my life has been influenced by knowing my dad as a counter-example. My understanding of his story was devised more by what he couldn’t do or say as by what he did. The silences in my father’s life had patterns, they made a legacy. Those silences told a story I’d listened to for years. 7. One of my favourite parts is the section in which you describe sex with a lesbian. You say, "We were still very queer . . . but . . . in that moment, I wanted to share myself with her authentically. I wanted her to see me." The whole book lets us see you. I'm always interested in asking memoir writers how they do that--how do you reconcile that wish to be seen with the human desire for privacy? Do you ever wish you had kept some of the story back, or did writing it transform it into something separate? I don’t have much of a wish for privacy. Maybe I would if there were reporters outside my door. So much of my early life was about hiding. As a kid, I hid my interest in boys, hid my tenderness, my parents’ fights, our poverty, my father’s drinking, my softness and vulnerability. I even hid my vocabulary, which put people off. Then as a teen I hid my orientation, and my body because it was too skinny. I hid my acne. I hid my facial hair and the fact that I shaved. I hid my body hair. I hid my boyfriend for nearly two years, at great expense and pains. So I don’t have much cause for hiding now that I’m an adult, and more secure in myself. Our vulnerabilities can make us loveable, and human, and safe. We don’t learn much by secreting ourselves away. Those silences only protect us when we’re deeply threatened. But I’m in a much better place in the world than I was as a kid, or as a teen. So I’m safe, and I can share, and I can make space for others to do the same. That’s how we learn best, by sharing. We’ve always progressed via generosity, via communication, via vulnerability. Those are the foundations of my writing.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

ALIX HAWLEYI'm the author of My Name is a Knife, All True Not a Lie In It, and The Old Familiar. Archives

February 2021

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed