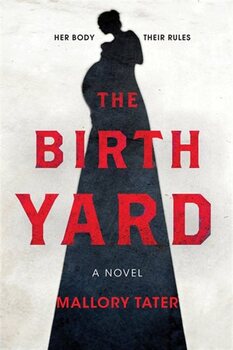

Mallory Tater's new novel, The Birth Yard, somehow feels exactly right for life in the coronaverse. It's set in claustrophobic confines, for one, where the outside world is made to feel extremely dangerous (and everyone wears the same clothes constantly . . . ). The cult known as The Den uses its female members for breeding. The women have been conditioned into contented acceptance, taking various drugs to control their fertility and moods. With her friends Dinah and Mamie, the book's protagonist, Sable Ursu, reaches breeding age, and the story follows her increasing unease during her "matching" with a man and subsequent pregnancy. Sable's slow movement from excitement to dull terror is one of this powerful novel's strongest feats (and I love Mallory's answer about teenage girls below). Mallory is also the author of the poetry collection This Will Be Good (Book*Hug Press 2018) and the publisher of Rahila’s Ghost Press, a poetry chapbook press. She lives in Vancouver with her husband and fellow writer, Curtis LeBlanc. I was happy she had some time to answer my questions --and that she got outside in this lovely dress for a photo! 1. Several generations of women in Sable’s family are present in the book, though her mother and Gram Evelyn are mainly in the background. We also see a little of Mamie’s mother and her difficulties. I’m interested in your ideas about lineage, especially for the novel’s women. I had a difficult time reconciling that, by the time the novel pivoted toward Part Two, there would be much less of Evelyn and Vale (Sable’s grandmother and mother). I tried to instill stories and tradition—kinship and ritual—between the women even though The Den discourages maternal relations of this kind. The moments in Part One where Sable, Evelyn and Vale sneak bread before dinner or chat about sexual intercourse or when Gram Evelyn shows Sable tarots, I hope, place those characters into Sable’s pocket to help her make the decisions she does at the Ceres Birth Yard in Part Two. Vale is much more traditional and obedient which kindles Sable’s kindness and sense of loyalty to her friends, while Evelyn’s rebelliousness, curiosity and slight devil-may-care attitude encourage Sable to channel her own thoughts and rhetoric into action when she is in the midst of injustices at her Birth Yard. Matrilineal lines inspire me greatly. When writing The Birth Yard, I had just undergone some family research of my own and travelled to Saskatchewan to learn about my great-great-great grandmother Elena Corches and my great-great grandmother, Rahila (her daughter). Rahila Corches (1888-1914), a young mother of three, immigrated from Campeni, Romania to Dysart, Saskatchewan with her husband, Samson, in hopes of finding stability, nourishment and safety. She helped her husband to build their sod house and maintain their emotional sense of home. She spent afternoons doing laundry and cooking with Canadian families in town to learn English. She died when she was twenty-six of unknown causes. In the St. George Romanian Orthodox Church in Dysart, Rahila Corches' death is listed as "extraordinary." Sable’s last name “Ursu” is actually named after my great-great Romanian Aunt Flossie who changed her maiden name Tater to Ursu. 2. “Natural” feminine qualities—domesticity, nurturing—are often part of real-life cults’ vision of how life should be. I like how the novel twists this idea. Can you talk about that? Basically, it was important for me to really lean into how Lynx and Feles [the cult leaders] and the ideology of The Den hold so much contradiction. Once the fear of their harsh punishments, sexist laws and false reverence are scraped away through Sable’s internal epiphanies and unlearning, it becomes clear, the men’s manipulations are out of their own fear of women, of being outsmarted by them. Feles isn’t super bright. He’s driven by narcissism and charisma. Narcissism and charisma can trick people into thinking someone knows best and someone is assertive and fair. It’s feigned intelligence. We’ve actually seen it in a raw, terrifying form in the US since November 2016 and it will only repeat itself so long as governments and work-forces are male-dominated. Well-known cults throughout history that have become household names, like Jonestown or the Branch Davidians or Children of God, hold this idea of bohemian, peaceful, utopic cooperation and use the ideas of nurturing, spirituality, selflessness and love to manipulate slave labour, physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as totalitarian final say on all matters. Feles has done the same, but also has to silence women who may also hold those qualities because he doesn’t see them as equal and doesn’t want men’s roles threatened or diluted by women’s voices or opinions. 3. Writers like Megan Abbott have talked about the weird power of teenage girls, and the way they’re culturally feared. I wonder if this was on your mind as you wrote. I love this question. I have actually always felt that popular culture doesn’t take care of our teenagers, particularly girls, in a lot of mainstream narratives. We ridicule their intense feelings, often making them the brunt of the joke in television and movies with their hormones, changing bodies and mood swings. Teenagers are actually so beautiful in their intriguing balance of caring what the entire world thinks of them while feeling unhinged and brave as they discover their identities and values. They’re children one moment and autonomous budding adults the next. Sable, Dinah and Mamie represent that crossroads of naivety blossoming into true growth. There is power in unlearning internalized sexism and taking ownership of your own body through expression and defiance. And there is a lit flame in those teenage years to take back what is yours loudly and in numbers. It’s amazing. I miss my teenage self and my friends holding such intense space and being so focussed on ourselves and what made us happy. I definitely enjoyed creating Sable’s circle of friendships throughout the novel. 4. Although it’s sometimes easy to forget these characters are teenagers, you’re very good at intense teenage feelings! Because the world of the novel is so closed, and the perspective tightly inside Sable, I wonder how it felt to plot the story in emotional currents? Thank you for the compliment. I think the pacing of Sable’s unravelling from The Den’s value system had to hold a lot of patience in order for me to feel like I got it right. My editors also really helped me ensure she wasn’t too defiant from Chapter 1. It’s a slow burn and it entails scenes in which her worldview is disillusioned—slowly with elements of her father forcing her to demand a courtship with Ambrose up until she is later physically shamed and abused with a spitting ritual for breaking rules. Also, I tried to remember the newness of her experiences such as flirting with a boy for the first time, drinking alcohol, losing her virginity, standing up to her father and all the raw, fragile dialogue, body language and emotion that would come with that. I really enjoyed delving into the thought process of Sable's younger sister, Kassia, because she, at fourteen, sees her sister as sort of a deity and places her on a pedestal. This helped me understand the significance of all of Sable’s firsts, how they would be so poignant in her world and the world of her sister and friends. 5. Sable’s "Match" Ambrose seems gentler than some of the men, especially the group leaders. What does life in the cult does to its male members? Ambrose is definitely kinder and less threatened by his own ego than some of the men in the novel, but he also has inklings of toxic leadership and entitlement that trickle into his mindset. For example, he doesn’t really seek justice for Sable after the spitting ceremony and likes the special attention he receives from the leaders because of his father’s status. The nuances of inherited gender roles and their toxicity become so ingrained, and the organization and othering of women so normalized, that it’s hard for boys in The Den to grow into empathetic and kind men. If you are taught that your gender is superior your entire life, even if you do grow to love and have friendships with women, they’ll still hold this societal power imbalance. Ambrose may not be as abusive and cruel as his peer, Isaac, Mamie’s match, but he still embraces and sets goals for himself which honour the toxic masculinity of The Den. 6. This book manages to feel removed from this world, yet contemporary. What made you choose the present tense? Present tense keeps an active voice that creates a sense of agency and immediacy. It honestly energizes me to keep on with the narrative because every scene feels very pressing and tense. It helps me because I actually don’t plan my fiction. I write as I go without a lot of direction so the present tense seems to help give me more agency to move the plot forward and to stay focussed. 7. What do you think gives Sable the internal power to start questioning her situation? I think there are many elements that lead up to Sable’s epiphany that The Den and all she knows is actually quite dark and harmful and sour. But one moment that I personally feel matters a lot to her is the risk of Dinah’s pregnancy and how Sable realizes Dinah can easily be discriminated against if her secret is found out. Sable sees Dinah as someone who is rebellious with her cuss words and clothes, but not someone who is deserving of grave punishment. She can’t reconcile that Dinah could be so severely hurt. I think Sable’s removal from school, her own punishments for rule breaking and her discovery of how severe the drug treatments at her Birth Yard are lead her to question and to seek justice and freedom. You can pick up or order the novel from your local independent bookstore (like Mosaic Books here in BC), Indigo, or Amazon.

0 Comments

|

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed