|

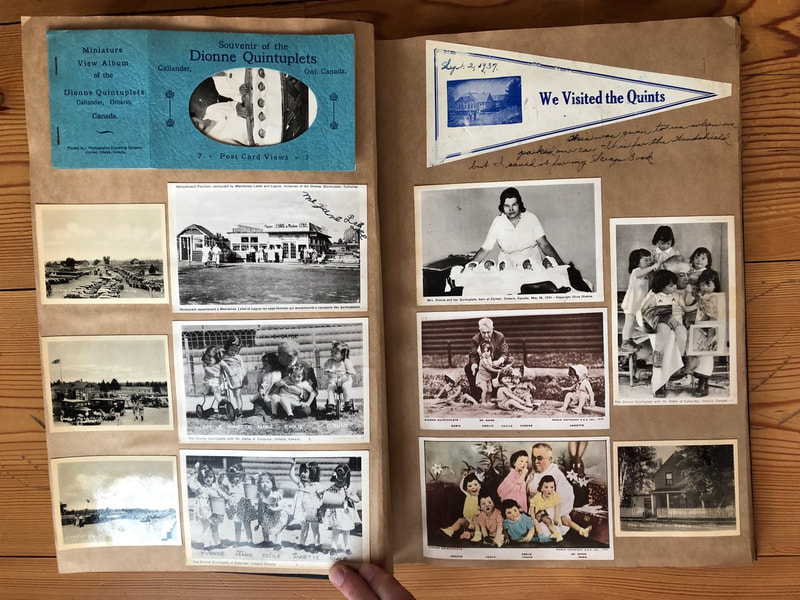

Like Clark Kent, Shelley Wood has cool glasses and secret superpowers. She's been a medical journalist for years, but has also more quietly been writing excellent short stories, and her first novel is out next week. The Quintland Sisters is about the so-famous-it-feels-like-a-movie birth of the identical Dionne quintuplets in rural Ontario in 1934. Partly in the form of a trainee midwife's diary, the book sinks into the five girls' earliest years and all the weirdness that surrounded them. It has a strong documentary feel, thanks to all Shelley's research (the Quints scrapbook above is part of her archival digging). She also has amazing ventriloquistic skills with her narrators--the main one, Emma Trimpany, is an invention, although I found myself Googling her just in case. Like I said, superpowers. Shelley is a fellow Okanagan resident, if a much more intrepid one than I am (she seems to be on top of Knox Mountain half the time, which may be why she has such a calm demeanour). When she was in drafting mode a couple of years ago, we bonded over our need to write a frame story that then has to be thrown out as you get towards what you really want to say. Shelley clearly got to the heart of what she wanted to with this beautifully written, sad, and thoughtful book. If you're in Kelowna, you can hear her read at her launch on March 5th. Other tour dates so far are here. 1. There's a quiet tension in the novel about world events of the 1930s. The narrator, Emma, blocks them out through her work nursing the quintuplets, sometimes almost obtusely. It made me think of Jane Austen being criticized for not writing more about war, etc., in her time; there's something a little Austenish about Emma (and not just her name). What's your view of her character? Oh, Emma. She thinks she knows everything, but is constantly bewildered when something unexpected happens. And perhaps like Austen’s Emma, she also sees the world she wants to see and convinces herself that she’s in the right. To me, she’s like most 17-year-old girls—self-possessed on the surface, but hopelessly unworldly. 2. The fascination with the Dionne Quintuplets has never gone away, although it's almost surprising to realize two of the women are actual people, still living. What's your sense of how this history became a myth so quickly? By 1934, when the babies were born, so many people had lost so much and their lives had become so hand-to-mouth, so dreary and desperate: they craved a real-world fairy-tale to lift them out of their day-to-day troubles. This was something the media, the government, and promoters of every stripe cottoned onto very quickly. I think the mythology around them was no accident; it was actively created by those who served to benefit. 3. Technical details! I'm so interested in the structure of this novel, which you set up as a file of documents--the overall diary, interspersed with newspaper articles and forms about the quintuplets, and finally a section of letters. Did you put it together in pieces? I explicitly set out to write an epistolary novel, made up of diary entries, letters, and other documents. It’s a format I love, not just because the reader gets to snoop through someone’s private papers, but also must work to fill in the gaps between the subjective and objective. Here, the letters and journal entries are fiction but the newspaper clippings, Blatz’s schedule, the Act for the Protection of the Dionne Quintuplets—these are all real, historic documents. And yet these are problematic too, the newspaper articles in particular, because far from being objective factual records, they were almost ludicrously biased, serving to continually stoke the public’s interest in this fairy-tale world. The timing of those final letters was also a choice. Most epistolary books that use letters to tell a story—think of Griffin and Sabine or The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society—provide both sides of the correspondence, chronologically. Instead, for most of The Quintland Sisters, the reader gets to see the letters that Emma has received, but they don’t get to read what she’s been writing in the letters she’s sending away. As a result, the letters at the end aren’t merely a replay, they are laced with all the prickling doubts that Emma couldn’t quite admit to herself, in her journals: they don’t tell quite the same story. 4. On that stylistic theme, I'm also curious about Emma's voice. Her diary feels removed from contemporary style, yet not "olde-timey," which isn't the easiest thing to do. How did it come to you? I wrestled, early on, with nailing a voice that was narrating events in the past tense, but always the very recent past—that day, that week—without the gloss of hindsight. Once I found that, Emma’s voice, which I wanted to have that diary-writer’s tone of confident self-consciousness, flowed pretty easily. 5. I can almost feel you pushing against expectations, especially in how the book deals with love. No spoilers, but I want to ask you whether that choice was deliberate. Absolutely! I knew almost from the start how I wanted the book to end for Emma, especially since the story of the quintuplets themselves continued on from here, tragically, and will likely never get a satisfying conclusion. The books I love most follow a pattern: they will always give you at least one thing that you’re desperately hoping for, but they won’t let you keep it. I aimed for that. 6. I like how you create a theme of birth and fertility beyond the quintuplets, straightforwardly and metaphorically. Can you talk about how you see that in the novel? Everyone who visited Quintland in the 1930s left with souvenir pebbles called Quint Stones that were supposed to bring good luck and fertility—as if those always go hand-in-hand. One of the themes I wanted to explore in this book was that of wanted and unwanted babies and, in tandem with that, wanted and unwanted motherhood. 7. The scientific and medical observation of the quintuplets is fantastically interesting as a document of the era. In your research, did you find any especially odd ideas about health or child-rearing (aside from corn syrup for babies!)? Dr. Allan R. Dafoe preached sunshine, cold air, and regular bowel movements, but he also signed up the quintuplets for endorsement deals for all sorts of health-giving products the girls likely never used or ate: Carnation Milk, Palmolive Soap, and Musterole Chest Rub, etc. But it was the child-rearing ideas of psychologist Dr. Blatz that I think were the most revolutionary for the day—he forbade spanking as punishment, but enforced a form of solitary confinement; he encouraged individualism, but discouraged the nurses from holding or soothing the girls. All these years later, Blatz’s books on the quintuplets are hard to stomach because he really did treat the girls as an experiment, where everything could be measured and tested and exposed to scientific inquiry. You can find The Quintland Sisters at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

1 Comment

Here's Emma Hooper, musician, novelist, knight. (Her musical project "Waitress for the Bees" has earned her a Finnish Cultural Knighthood.) She's also an expat Canadian living in Bath, UK, but I got to meet her on this side of the Atlantic at the 2015 Amazon First Novel Awards, where she read from her bestselling Etta and Otto and Russell and James. I was happy to see her (and her well-travelled baby) again last fall at the Vancouver Writers Festival. This time she pleased the crowd with part of her new book, Our Homesick Songs -- "a brilliant and tender dream," says Affinity Konar. It is that, but like Emma, and like its child characters, this book has a smart, slightly mischievous energy. Our Homesick Songs manages to be about the exodus of Newfoundland workers to Alberta, and also not quite fully of this world. It's filled with tiny perfections, like the pseudonym of "Don" for a teenage girl, who in turn names her wolflike dogs Giannina and Giancarlo. It folds in smaller stories, too, including one about how the snakes left Ireland, and the tales in old songs like The Water is Wide, which she talks about below. (Continuing the home-leaving theme, she'll be teaching a course in Italy this summer on Perfecting Your Prose. No envy here, none at all.) The image on the right is from Mark Clintberg's work, Not the one but there is no one else, which influenced Emma, and feels like a visual conjuring of her novel. (Clintberg is an artist friend of hers who made the piece in Newfoundland.) Watching Emma knit and manage all the book's nets is delightful. Here's what she had to say about writing and about being a semi-abandoned child of the '80s. 1. This novel is set in the 1970s and the 1990s, in Newfoundland and in the Alberta Oil Patch. So far, so grim, right? Yet this book is in no way grim, despite the economic anxieties and family problems it portrays. Can you describe your view of the tone? I think a simple way of describing it would be “hopeful.” The book is very much about a champion for hope, and hope for hope’s sake. The two child-protagonists, Cora and Finn, have very different plans and ideas, one quite gritty and realist, and one, well, not, but the hope they share is the same. It lots of ways the book is about looking back, to ancestry, cultural heritage, folklore . . . but it’s also about balancing that out by looking forward: to hope, the thing that pulls us forward. 2. I'm sure every interview asks you about music! Did you find musical structure influenced the novel's back-and-forth structure? And does any particular song go with this book for you? The folk songs in the book all have at least a bit of thematic significance individually, with The Water is Wide being perhaps the most potent. It’s a folk song so old and so scattered in lineage that you can’t actually trace it back to any one person or place, it’s a mosaic of a cultural artefact, passed down and pieced together by many different hands from different lands (I just made that up but it sounds like a saying, doesn’t it? Ha!). That’s an idea that important, central, even, to the book. As for musical structure, well, I do love to play with both white space and the back and forth of time and voice in a way that it’s likely my musical background underscores. It’s also, hopefully, a bit reminiscent of the inescapable sound of the wind and the waves in places like the outport community where Our Homesick Songs is set. A sort of melody-less song of itself. 3. On that note, I love the way the kids, Cora and Finn, are always practicing. The instruments are constants when their lives turn uncertain, but you're not sentimental about it. I'm especially interested in your portrayal of the tie between Finn and his accordion teacher. Can you talk about that? As a kid learning violin, my parents used to say I only had to practice on the days I ate. I wanted to represent this idea of a deep-rooted musical community, where making music isn’t a flashy or showy thing at all, no stages involved, just something natural that people do, that people have to do, that people have always done and will always do. 4. I kept thinking about parallel existences and other possible lives for these characters, which they think about too. How do you see that playing out in the settings--Big Running and Little Running, St John's and Alberta work camps-- which you describe quite differently? Anyone who has moved away from their hometown (or home country, even more so) knows the feeling of having to reassess what it is, exactly, that makes you you. The paired excitement of being able to be anyone or anything, being free from expectation and tradition, and, at the same time feeling somehow more bound by that tradition, that nostalgic idea of home, than ever before. I wanted to explore that liminal place in the book, especially with Cora, who, at 14, is also dealing with the overhauling of identity that comes with adolescence . . .. 5. This book walks the line between magical and realistic, and you stay just this side of magic. Can you discuss that a little? I think hope itself often walks this line, between magic and realism, and, at times, allowing ourselves hope can seem as fruitless or difficult as believing in magic, so it made sense for me to blend the lines between the two here, in this book. Also, much of the magical thinking and hoping comes from Finn, who, at 11, is in that in-between place himself, between the magical beliefs and ease of childhood and the realism of adulthood, so it made sense to me that his stories and plans should reflect that tension. 6. It's also about family history and different generations, like many novels, and there's certainly conflict, but to me, that's not the book's point, or its power. Does the title play into that, for you? Yep, certainly. The title, Our Homesick Songs, is a reference to an idea that comes up in the book, that ‘all songs are homesick songs’, meaning all songs—or music, really—has the power to transport us into our own past, in a Proustian Madeleine kind of way. Only I’ve extended that idea of person past to include our ancestral and cultural pasts too, songs, therefore, have to ability to connect us with our family and extended-community family over both space and time . . .. 7. Like you, I have young kids, and I'm envious of--or homesick for--these '70s and '90s parents who let their children go boating alone and wander around outside all day, etc.! Was that on your mind? Ha ha, yes! And '80s parents too, aka mine . . . I spent a crazy amount of time out exploring the woods and ravines around our house as a kid; it was amazing, of course, at least in retrospect. When I think of it as a parent it’s also terrifying, of course . . .. As for the characters in the book, well, I guess there’s a reason why most child-heroes are orphans, or at least semi-abandoned. The freedom gives them agency, as well as the time to hatch and follow-through ambitious, over-the-top, schemes and plans. You can buy the book at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

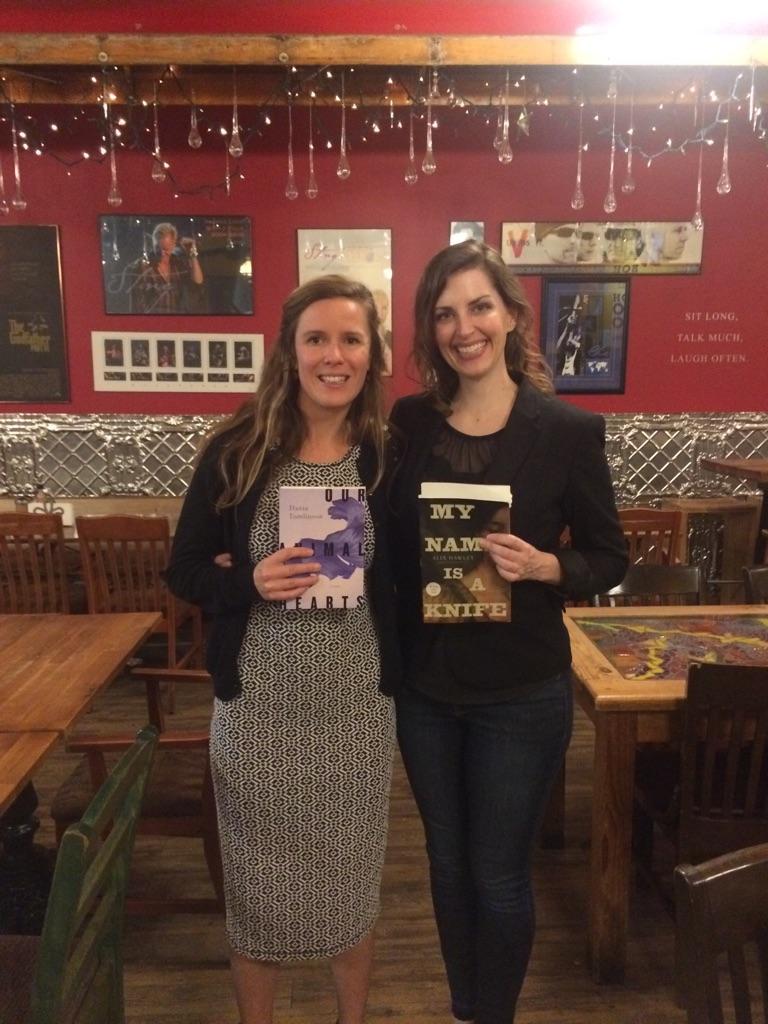

The various faces of Dania Tomlinson! A fellow Canadian writer and mother (more on that in the interview), she was kind enough to be the opening act at the hometown launch for My Name is a Knife in September. And look at her beautiful novel, which Canadian Living named a top book of 2018. (On the right, it's looking all fancy in the store this week.)

Our Animal Hearts is her first novel. It has a deceptively pretty sheen. Beneath, it's a kind of excavation, a mystery / history of the Okanagan Valley (traditional territory of the Syilx / Okanagan people), and full of passionate writing and characters. Its turn-of-the-20th-century setting evokes how weird this place can feel beneath its own prettiness, and how weirdly and precariously the layers of its past sit on each other. The opening line is, "This lake has no bottom." The power of the wilderness is probably *the* Canadian Literature cliche, and I think Dania takes that on purposely. She has several fresh twists, including a monster that haunts people's dreams as well as the lake it has lived in for centuries. It floats in and out of the story's reality, and one of the things I love about this book is its overlaying of realities (not least the Indigenous and settler worlds), as I asked her about below. Gothic fans, this one is for you. But it's for psychological realism fans too. Maybe something like Alice Munro moving into Castle Rackrent. Dania grew up in the valley and earned her MFA at UBC. She's been writing for years; she worked on this book for ten. It's a little hard to reconcile her in-person joyful energy with the dark power of her novel. But that's one of my favourite dichotomies. 1. Your novel is set in the Okanagan Valley in BC, but also not--there's a half-real world that sometimes overlaps it pretty matter-of-factly. Can you tell me about how that works here? I think in terms of the "half-real world’" what I had in mind was more of an internal world--a world that is in fact very real, but just unseen. A personal, internal world, where our imaginings, our thoughts, our histories are made manifest. I was often asking myself: What if this fantasy/thought/fear was made physical? What would that look like? We all exist in our own version of reality, where are thoughts, memories, imaginings, are almost tangible. For example, in the Okanagan, the threat of a cougar following me through the forest is a very real possibility. And my imagination has always been a little obsessed with that. I picture this cougar following me. I can see it perfectly--velvet fur, yellow eyes. It disappears whenever I turn to look, but it is almost real. The fear of it though, is undeniable. 2. The epigraph is from the Welsh epic The Mabinogion, a work that's significant in the novel too. Do you remember when you first read it, and whether it influenced your structure or writing? I stumbled across The Mabinogion late in the editing process. I was well into my second or third draft with my editor and was researching Blodeuwedd, a man-made woman who is turned into an owl by her jealous husband. The Mabinogion is an English translation of ancient Welsh stories, many of which were first recorded in the Red Book of Hergest. Finding this text was like magic. As though someone in the 1300’s recorded these oral stories just for me. When I found water creatures in The Mabinogion, I nearly lost my mind. This text was a missing piece for Our Animal Hearts. Reading it gave me a fresh rush of energy for a story I had been writing and rewriting for nearly ten years. I’m not sure it really influenced the structure of Our Animal Hearts, although including The Mabinogion as a physical book in the novel allowed me to expand on a theme I was already interested in: storytelling, the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell others about ourselves, the stories that we remember, and most importantly, the stories that haunt us. I was already writing in parallel to this text without even knowing it. It was eerie. I still have goosebumps. 3. Speaking of the epigraph, it includes the lines, "There are no rude wants / With creatures." Animals, real and magically real, dead and alive, populate the book. How did that come about? Growing up so close to forests and lakes has made it impossible for me to imagine a world without animals. We see them everywhere and yet they exist in another realm; they’re like spirits. Animals are so unknowable, so beautiful, and so mysterious. And then there are animals that seem actually unreal to me, like peacocks. These birds are too ridiculous, too fabulous, to be real. Someone once used the word “animism” to describe the animal presence in Our Animal Hearts, but I don’t think that’s quite it. I like to tell a couple stories in response to questions about the animals. The first is about the cougar I already described. The second is that long before my grandmother died (the Welsh one) she said that after death she would come back as a blue heron. Now, since she’s died, my mom and I see blue herons everywhere. And it’s not that I really think my grandmother has come back as a blue heron (though, who knows!), but what matters is that when I see a blue heron I am mystified, and I think of her, and I am in wonder and awe. The bird has such weight that it has become a kind of symbol or saint to me. 4. The book is so much about various cultures bumping up against each other in one place: Indigenous, European, Japanese. What was it like to try to blend them? I think blending cultural stories more honestly portrays the human experience. We aren’t limited to only, for example, Biblical stories, or Welsh stories. In a globalized world, we come into contact with myths, legends, and fairy tales of various backgrounds; personal stories; histories; movies; songs; etc. etc. We are each influenced by limitless stories and often build up allusions and make connections willy-nilly. I like to use the term "mongrel stories" though I’m not sure that’s quite right. I think sharing stories and finding value and building connections between different cultural and personal stories might be a fruitful way forward in a world where there is often a lot of segregation and misunderstanding. 5. There's a lot about reading here, with many references to Iris's childhood reading, and to a private library, and to trying to learn words from other languages. I'm interested in your thoughts about that. This motif goes back to my obsession with storytelling. What stories influence us? How do we tell those stories? We always add our own personal slant when we tell a story. We absorb stories when we allow them in. We can’t help but alter them as they alter us. And then how are those stories communicated? Do they need to be told orally? What happens when they are written down? How does language limit our ability to share stories? Does a story lose meaning in a different language? What stories are inexpressible? What stories are only internal ones that we tell ourselves, that we have no language for? 6. Iris is the main character and the speaker, but her mother, Llewelyna, almost takes over the story, and maybe she's why you refer to the Welsh tale of Rhiannon eating her children. Can you talk about the push and pull between parents and children in the book? And maybe between siblings too? I like the connection that you made there. I find the Rhiannon story fascinating on many levels. It’s a story about storytelling, too! I am fascinated by motherhood, especially unwilling mothers or mothers whose personal lives are mysterious and disturbing to their children. Llewelyna is at the extreme end of the unwilling mother scale. That said, a mother’s love is often ferocious and not unlike hunger--not unlike a desire to devour. I love my daughter so much I could bite her. (But I don’t; promise.) 7. One of the lines that stays with me is, "Every few years someone disappears in the lake." Nightmares! Having grown up in the Okanagan too, I've always been obsessed with the lake and the monster and the stories about vanished bodies, and I wonder whether your own childhood thinking is in the book. My childhood is all over this book; it’s gone feral on these pages. My imagination was frantic as a kid, and to be honest it has lost little of its enthusiasm. I find that the story of the lake monster is rarely ever "told" to you, not in so many words. Instead, the lake monster has always already existed. It’s usually more something you learn when you overhear someone who is pointing out into the middle of the lake saying: “Look! There it is! It’s coming this way.” |

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed