|

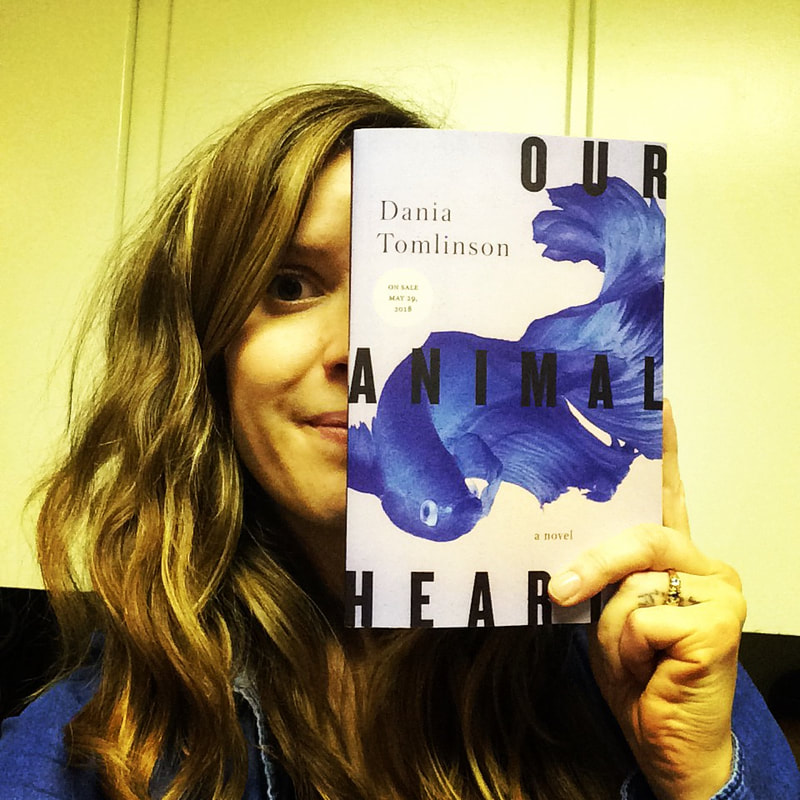

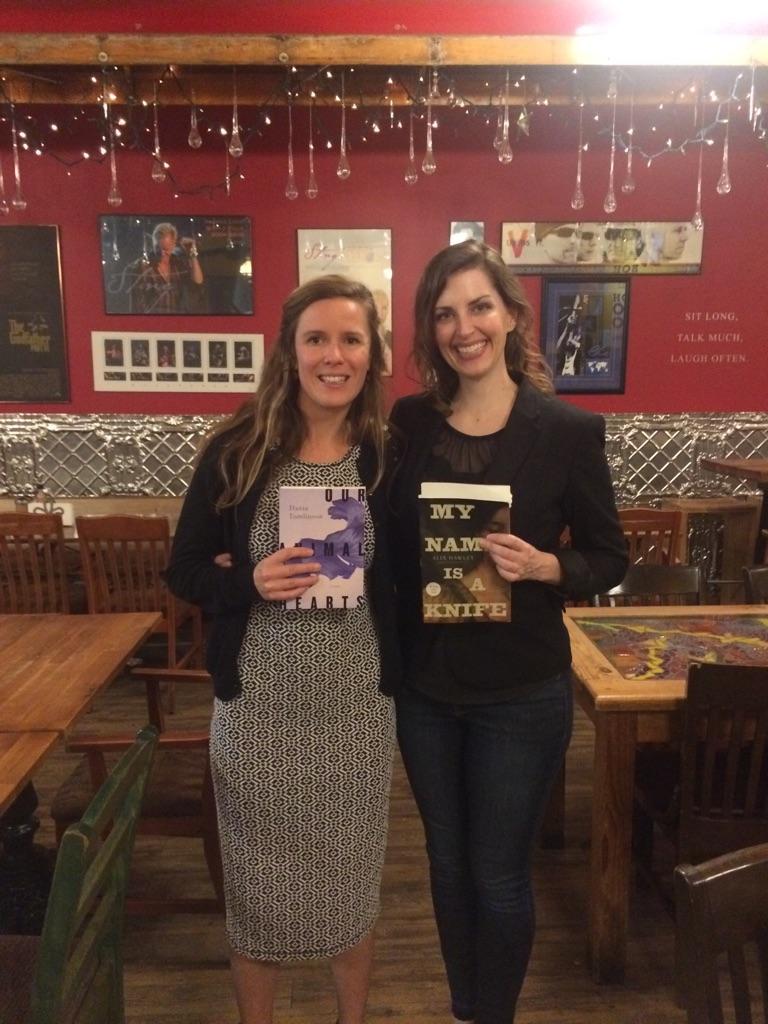

The various faces of Dania Tomlinson! A fellow Canadian writer and mother (more on that in the interview), she was kind enough to be the opening act at the hometown launch for My Name is a Knife in September. And look at her beautiful novel, which Canadian Living named a top book of 2018. (On the right, it's looking all fancy in the store this week.)

Our Animal Hearts is her first novel. It has a deceptively pretty sheen. Beneath, it's a kind of excavation, a mystery / history of the Okanagan Valley (traditional territory of the Syilx / Okanagan people), and full of passionate writing and characters. Its turn-of-the-20th-century setting evokes how weird this place can feel beneath its own prettiness, and how weirdly and precariously the layers of its past sit on each other. The opening line is, "This lake has no bottom." The power of the wilderness is probably *the* Canadian Literature cliche, and I think Dania takes that on purposely. She has several fresh twists, including a monster that haunts people's dreams as well as the lake it has lived in for centuries. It floats in and out of the story's reality, and one of the things I love about this book is its overlaying of realities (not least the Indigenous and settler worlds), as I asked her about below. Gothic fans, this one is for you. But it's for psychological realism fans too. Maybe something like Alice Munro moving into Castle Rackrent. Dania grew up in the valley and earned her MFA at UBC. She's been writing for years; she worked on this book for ten. It's a little hard to reconcile her in-person joyful energy with the dark power of her novel. But that's one of my favourite dichotomies. 1. Your novel is set in the Okanagan Valley in BC, but also not--there's a half-real world that sometimes overlaps it pretty matter-of-factly. Can you tell me about how that works here? I think in terms of the "half-real world’" what I had in mind was more of an internal world--a world that is in fact very real, but just unseen. A personal, internal world, where our imaginings, our thoughts, our histories are made manifest. I was often asking myself: What if this fantasy/thought/fear was made physical? What would that look like? We all exist in our own version of reality, where are thoughts, memories, imaginings, are almost tangible. For example, in the Okanagan, the threat of a cougar following me through the forest is a very real possibility. And my imagination has always been a little obsessed with that. I picture this cougar following me. I can see it perfectly--velvet fur, yellow eyes. It disappears whenever I turn to look, but it is almost real. The fear of it though, is undeniable. 2. The epigraph is from the Welsh epic The Mabinogion, a work that's significant in the novel too. Do you remember when you first read it, and whether it influenced your structure or writing? I stumbled across The Mabinogion late in the editing process. I was well into my second or third draft with my editor and was researching Blodeuwedd, a man-made woman who is turned into an owl by her jealous husband. The Mabinogion is an English translation of ancient Welsh stories, many of which were first recorded in the Red Book of Hergest. Finding this text was like magic. As though someone in the 1300’s recorded these oral stories just for me. When I found water creatures in The Mabinogion, I nearly lost my mind. This text was a missing piece for Our Animal Hearts. Reading it gave me a fresh rush of energy for a story I had been writing and rewriting for nearly ten years. I’m not sure it really influenced the structure of Our Animal Hearts, although including The Mabinogion as a physical book in the novel allowed me to expand on a theme I was already interested in: storytelling, the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell others about ourselves, the stories that we remember, and most importantly, the stories that haunt us. I was already writing in parallel to this text without even knowing it. It was eerie. I still have goosebumps. 3. Speaking of the epigraph, it includes the lines, "There are no rude wants / With creatures." Animals, real and magically real, dead and alive, populate the book. How did that come about? Growing up so close to forests and lakes has made it impossible for me to imagine a world without animals. We see them everywhere and yet they exist in another realm; they’re like spirits. Animals are so unknowable, so beautiful, and so mysterious. And then there are animals that seem actually unreal to me, like peacocks. These birds are too ridiculous, too fabulous, to be real. Someone once used the word “animism” to describe the animal presence in Our Animal Hearts, but I don’t think that’s quite it. I like to tell a couple stories in response to questions about the animals. The first is about the cougar I already described. The second is that long before my grandmother died (the Welsh one) she said that after death she would come back as a blue heron. Now, since she’s died, my mom and I see blue herons everywhere. And it’s not that I really think my grandmother has come back as a blue heron (though, who knows!), but what matters is that when I see a blue heron I am mystified, and I think of her, and I am in wonder and awe. The bird has such weight that it has become a kind of symbol or saint to me. 4. The book is so much about various cultures bumping up against each other in one place: Indigenous, European, Japanese. What was it like to try to blend them? I think blending cultural stories more honestly portrays the human experience. We aren’t limited to only, for example, Biblical stories, or Welsh stories. In a globalized world, we come into contact with myths, legends, and fairy tales of various backgrounds; personal stories; histories; movies; songs; etc. etc. We are each influenced by limitless stories and often build up allusions and make connections willy-nilly. I like to use the term "mongrel stories" though I’m not sure that’s quite right. I think sharing stories and finding value and building connections between different cultural and personal stories might be a fruitful way forward in a world where there is often a lot of segregation and misunderstanding. 5. There's a lot about reading here, with many references to Iris's childhood reading, and to a private library, and to trying to learn words from other languages. I'm interested in your thoughts about that. This motif goes back to my obsession with storytelling. What stories influence us? How do we tell those stories? We always add our own personal slant when we tell a story. We absorb stories when we allow them in. We can’t help but alter them as they alter us. And then how are those stories communicated? Do they need to be told orally? What happens when they are written down? How does language limit our ability to share stories? Does a story lose meaning in a different language? What stories are inexpressible? What stories are only internal ones that we tell ourselves, that we have no language for? 6. Iris is the main character and the speaker, but her mother, Llewelyna, almost takes over the story, and maybe she's why you refer to the Welsh tale of Rhiannon eating her children. Can you talk about the push and pull between parents and children in the book? And maybe between siblings too? I like the connection that you made there. I find the Rhiannon story fascinating on many levels. It’s a story about storytelling, too! I am fascinated by motherhood, especially unwilling mothers or mothers whose personal lives are mysterious and disturbing to their children. Llewelyna is at the extreme end of the unwilling mother scale. That said, a mother’s love is often ferocious and not unlike hunger--not unlike a desire to devour. I love my daughter so much I could bite her. (But I don’t; promise.) 7. One of the lines that stays with me is, "Every few years someone disappears in the lake." Nightmares! Having grown up in the Okanagan too, I've always been obsessed with the lake and the monster and the stories about vanished bodies, and I wonder whether your own childhood thinking is in the book. My childhood is all over this book; it’s gone feral on these pages. My imagination was frantic as a kid, and to be honest it has lost little of its enthusiasm. I find that the story of the lake monster is rarely ever "told" to you, not in so many words. Instead, the lake monster has always already existed. It’s usually more something you learn when you overhear someone who is pointing out into the middle of the lake saying: “Look! There it is! It’s coming this way.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed