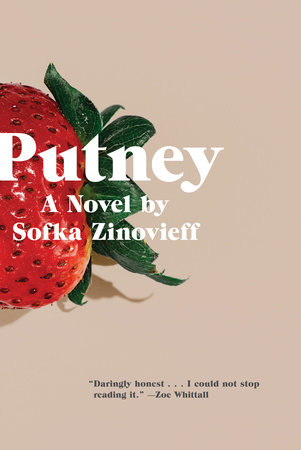

I met Sofka at the Vancouver Writers Festival in October, where we were among the readers at the Afternoon Tea event (there she is at left on Granville Island, the venue, where even the weather cooperated). She read from her new novel, Putney, and the excerpt she gave in her beautiful voice gripped the room--a scene in which the 13-year-old Daphne is newly arrived in Greece with Ralph, her father's friend and secretly her "boyfriend." I picked up my copy immediately, and couldn't stop reading. Putney dives straight into the barbed wire of historical sexual abuse, how it's revealed, and how different genders and generations can react to it. The Guardian calls it "a Lolita for the age of #MeToo." With three narrative streams (Daphne's, Ralph's, and Daphne's friend Jane's), it slides easily between perspectives, a technical feat as well as a bold one. It's just been selected as an Observer Book of the Year, and is also a top pick in The New Statesman and The Spectator. Sofka's writing is elegant (as is she!). She's a journalist as well as a novelist, as the clarity of her prose shows. I was so pleased to speak with her about it. Putney is your title, with all the protagonists associate with that riverside London neighbourhood from their earlier lives. But Greece is a stronger force in the novel, in some ways. Did it symbolize anything for you in writing? Yes! I’d say this reflects something about my own life, as Greece has been such a strong force for me. I lived there as an anthropology research student and have been closely involved ever since. I eventually married a Greek and we have two bi-cultural daughters, who went to school in Greece. In Putney, I see Greece as symbolizing the place that Daphne is able to start anew and find a positive way of going forward after all her traumas. Putney is also the title of one of Daphne's fantastical fabric sculptures, which she comes to see very differently through the novel. You include a couple of passing moments of Ralph's thoughts on art by women, and his mindset seems to affect Daphne sometimes too. Can you talk about that? Ralph is very dismissive about what he sees as Daphne’s feminine work that uses fabrics (and other materials) for collages and hangings. He feels it’s not serious – drenched in estrogen! I suspect that some men are snobbish about “women’s work” or art that overlaps with craft. This was also an opportunity for the cultured, charismatic, successful Ralph to reveal himself as a snobbish bigot. I’m not sure whether his mindset affects the adult Daphne vis-à-vis her art, but she begins the books creating a sort of homage to her childhood and teen years and her love for Ralph. Later, she feels very differently, recognizing that she has honoured the man who abused her. The book is about age versus youth, adults versus children, but also specifically about hippie, arty Baby Boomers versus their children. One of the book's most devastating scenes includes Daphne's aged father's reaction to her telling him about her childhood abuse. I'm interested in that moment, and how she gets past it, and in your thoughts. -Daphne’s father has always loved his daughter, but he has also been neglectful. He didn’t notice when his friend was seducing his underage teenage daughter in the 1970s and he was too wrapped up in his work and his own affairs to pay attention. This egocentricity continues into old age, where he is unable to face up to Daphne’s suffering and her reassessment of what happened to her as child sexual abuse. Perhaps this is because he would have to reassess his entire life, so he is happier to look away and choose not to fully understand. It is his way of maintaining an equilibrium towards the end of his own life and perhaps reflects his fear that otherwise the fall-out could be devastating to him too. The shifting points of view give the novel its intensity. Did you know from the start you would write with three different viewpoints, all in third person? Did you try at all in first person? I always knew there would be two viewpoints of Daphne and her older lover Ralph, but Jane (as friend and witness) came in pretty early as an idea and I was quickly convinced of the book’s need for someone outside the heated [relationship]. I wondered about writing in the first person, but I was happier to keep a more unified narrative voice that comes with several characters having a close third person. More specifically, was it difficult to write from Ralph's point of view? I wonder what it was like to hear and express his way of thinking as you wrote. I found it almost worryingly easy to sit inside Ralph’s head! I’m afraid it’s because I’ve known several men who have certain characteristics of Ralph. His charm, deceptions and justifications just flowed. Jane is, to my mind, the most powerful character, and not just because of what she knows. I found myself alternately drawn in and repelled by her. Perhaps the negative reaction comes from her own feelings about her younger self, which you draw so strongly. Can you discuss your feelings about her? Jane is ostensibly the sensible, ethical character who calls out Ralph as the abuser he so clearly is, but that Daphne doesn’t initially recognize, even after decades. But ultimately, Jane is far from being a reliable narrator. One aspect of that is the envy she felt towards Daphne when they were young and the on-going insecurities about herself and her body, despite her success in her professional and family life. Another aspect is that she is not being entirely honest, even to herself, about her motives. Some readers are irritated by her, perhaps because of her dogged determination to persuade Daphne to go to the police and denounce the man she believed she loved all those decades earlier. Technical question: what was the first scene you drafted? Did it remain in the final version? I wrote several scenes before I started at the beginning. The first was when Ralph goes to Daphne’s house in the famously hot summer of 1976. He is collecting her so they can travel to Greece together on the hippy-ish Magic Bus – a trip that will end with them sleeping together for the first time. I wanted to bring out the extraordinary ability of young girls to veer between childhood and womanhood, so that there is something confusing to both the girl and the observer. It is this tendency that the adult Daphne later witnesses in her own daughter and that helps her to realize that a 13-year-old may play about with sexuality, but she is still a child.

0 Comments

|

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed