|

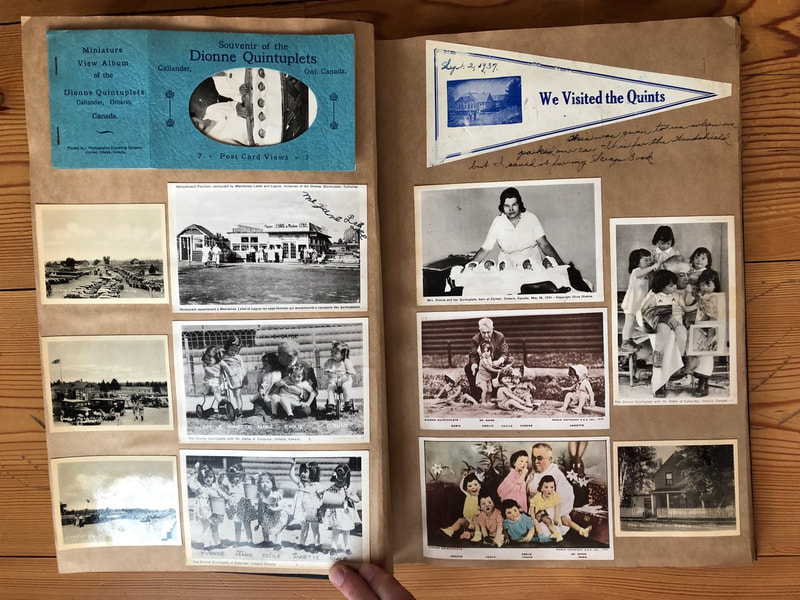

Like Clark Kent, Shelley Wood has cool glasses and secret superpowers. She's been a medical journalist for years, but has also more quietly been writing excellent short stories, and her first novel is out next week. The Quintland Sisters is about the so-famous-it-feels-like-a-movie birth of the identical Dionne quintuplets in rural Ontario in 1934. Partly in the form of a trainee midwife's diary, the book sinks into the five girls' earliest years and all the weirdness that surrounded them. It has a strong documentary feel, thanks to all Shelley's research (the Quints scrapbook above is part of her archival digging). She also has amazing ventriloquistic skills with her narrators--the main one, Emma Trimpany, is an invention, although I found myself Googling her just in case. Like I said, superpowers. Shelley is a fellow Okanagan resident, if a much more intrepid one than I am (she seems to be on top of Knox Mountain half the time, which may be why she has such a calm demeanour). When she was in drafting mode a couple of years ago, we bonded over our need to write a frame story that then has to be thrown out as you get towards what you really want to say. Shelley clearly got to the heart of what she wanted to with this beautifully written, sad, and thoughtful book. If you're in Kelowna, you can hear her read at her launch on March 5th. Other tour dates so far are here. 1. There's a quiet tension in the novel about world events of the 1930s. The narrator, Emma, blocks them out through her work nursing the quintuplets, sometimes almost obtusely. It made me think of Jane Austen being criticized for not writing more about war, etc., in her time; there's something a little Austenish about Emma (and not just her name). What's your view of her character? Oh, Emma. She thinks she knows everything, but is constantly bewildered when something unexpected happens. And perhaps like Austen’s Emma, she also sees the world she wants to see and convinces herself that she’s in the right. To me, she’s like most 17-year-old girls—self-possessed on the surface, but hopelessly unworldly. 2. The fascination with the Dionne Quintuplets has never gone away, although it's almost surprising to realize two of the women are actual people, still living. What's your sense of how this history became a myth so quickly? By 1934, when the babies were born, so many people had lost so much and their lives had become so hand-to-mouth, so dreary and desperate: they craved a real-world fairy-tale to lift them out of their day-to-day troubles. This was something the media, the government, and promoters of every stripe cottoned onto very quickly. I think the mythology around them was no accident; it was actively created by those who served to benefit. 3. Technical details! I'm so interested in the structure of this novel, which you set up as a file of documents--the overall diary, interspersed with newspaper articles and forms about the quintuplets, and finally a section of letters. Did you put it together in pieces? I explicitly set out to write an epistolary novel, made up of diary entries, letters, and other documents. It’s a format I love, not just because the reader gets to snoop through someone’s private papers, but also must work to fill in the gaps between the subjective and objective. Here, the letters and journal entries are fiction but the newspaper clippings, Blatz’s schedule, the Act for the Protection of the Dionne Quintuplets—these are all real, historic documents. And yet these are problematic too, the newspaper articles in particular, because far from being objective factual records, they were almost ludicrously biased, serving to continually stoke the public’s interest in this fairy-tale world. The timing of those final letters was also a choice. Most epistolary books that use letters to tell a story—think of Griffin and Sabine or The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society—provide both sides of the correspondence, chronologically. Instead, for most of The Quintland Sisters, the reader gets to see the letters that Emma has received, but they don’t get to read what she’s been writing in the letters she’s sending away. As a result, the letters at the end aren’t merely a replay, they are laced with all the prickling doubts that Emma couldn’t quite admit to herself, in her journals: they don’t tell quite the same story. 4. On that stylistic theme, I'm also curious about Emma's voice. Her diary feels removed from contemporary style, yet not "olde-timey," which isn't the easiest thing to do. How did it come to you? I wrestled, early on, with nailing a voice that was narrating events in the past tense, but always the very recent past—that day, that week—without the gloss of hindsight. Once I found that, Emma’s voice, which I wanted to have that diary-writer’s tone of confident self-consciousness, flowed pretty easily. 5. I can almost feel you pushing against expectations, especially in how the book deals with love. No spoilers, but I want to ask you whether that choice was deliberate. Absolutely! I knew almost from the start how I wanted the book to end for Emma, especially since the story of the quintuplets themselves continued on from here, tragically, and will likely never get a satisfying conclusion. The books I love most follow a pattern: they will always give you at least one thing that you’re desperately hoping for, but they won’t let you keep it. I aimed for that. 6. I like how you create a theme of birth and fertility beyond the quintuplets, straightforwardly and metaphorically. Can you talk about how you see that in the novel? Everyone who visited Quintland in the 1930s left with souvenir pebbles called Quint Stones that were supposed to bring good luck and fertility—as if those always go hand-in-hand. One of the themes I wanted to explore in this book was that of wanted and unwanted babies and, in tandem with that, wanted and unwanted motherhood. 7. The scientific and medical observation of the quintuplets is fantastically interesting as a document of the era. In your research, did you find any especially odd ideas about health or child-rearing (aside from corn syrup for babies!)? Dr. Allan R. Dafoe preached sunshine, cold air, and regular bowel movements, but he also signed up the quintuplets for endorsement deals for all sorts of health-giving products the girls likely never used or ate: Carnation Milk, Palmolive Soap, and Musterole Chest Rub, etc. But it was the child-rearing ideas of psychologist Dr. Blatz that I think were the most revolutionary for the day—he forbade spanking as punishment, but enforced a form of solitary confinement; he encouraged individualism, but discouraged the nurses from holding or soothing the girls. All these years later, Blatz’s books on the quintuplets are hard to stomach because he really did treat the girls as an experiment, where everything could be measured and tested and exposed to scientific inquiry. You can find The Quintland Sisters at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

1 Comment

Al

3/27/2020 08:08:26 pm

Just to clarify did Emma’s family pass in the

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed