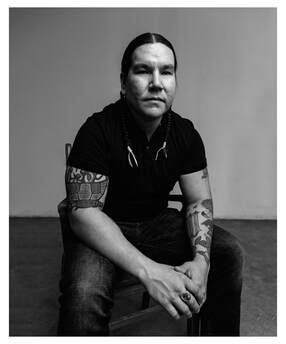

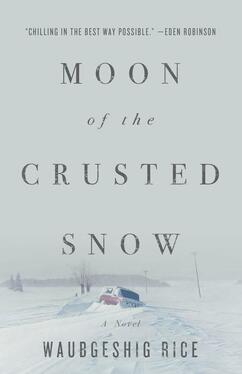

Photo credit: Rey Martin Photo credit: Rey Martin This fall, Waubgeshig Rice and I hung out in a lot of elevators at festival venues. It was always great to see his grin at various points on the road! We were both on the Cabaret bill at the Kingston Writers' Festival, where all the writers performed with live jazz backup, and Waub read from his newest novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow. Ontario CBC listeners get to hear Waub's voice all the time on Up North, but they don't often get to hear the show host read his fiction. He held the Kingston audience with the deceptively casual style of his reading--one of those sessions when you can feel the hook slowly pierce the room, and the entire group lets its breath out at the end. The quietly written, sharply outlined vision of life post-apocalypse depicts a northern First Nation family, Evan and Nicole and their two small children, trying to keep a community intact as things fall apart. I read it this winter, and though we're beyond the Anishinaabe late winter / early spring crusted snow moon now, the book hasn't let my mind go. Waub, a member of the Wasauksing First Nation, is a longtime journalist as well as a writer of short fiction and novels, and I'm glad to know he's working on a longer nonfiction project now. (Hurry up!) I'm grateful he had time to answer some questions about writing this book (and a little PJ Harvey on the soundtrack never goes amiss). 1. You're really good at quiet dread. I'd like to know how it felt to keep the tension up in writing this book, which is so much about everyday life in spite of some kind of disaster. Thank you, Alix! I’m glad you appreciated the building tension in the book. The story is more of a slow burn due to its rural and distant setting, so it was a challenge to keep that suspense building steadily throughout, even when there wasn’t much “happening”. A crisis due to a power and communications outage would unfold much more quickly in an urban setting, but this story takes place in a northern First Nation, where panic wouldn’t set in so soon due to the slower pace of life and the ability to adapt. And it was important for me to reflect that everyday life in this community, which is about close relationships with each other and the land, and less reliance on technology and infrastructure than in the city. Still, those luxuries have played an increasing role in the daily life of this First Nation, which is where that tension originally begins. Confusion arises around what prompted the blackout, if and when food and supplies will arrive from the south, and whether everything would come back online. Anyone who thinks long and hard enough about that kind of scenario would surely frighten themselves! So writing this story definitely became a tense exercise for me. I often asked myself what I’d do in that situation for my own family, and whether I’d actually be prepared for the end of the world as we know it. But in the end, I knew the resolution I wanted to come to with this story, and that kept me hopeful and at ease. The tension ultimately leads to another future, which is something that’s kind of exciting to consider. 2. Another part of the novel's structure is its representation of colonialism in miniature, with the white man Scott turning up looking for harbour. It would be easy to make Scott (whose name conjures up the British Antarctic explorer) a parody villain--just a one-note Bad Guy--but he's genuinely frightening because of how specifically you've drawn him. Can you tell me about writing him? I really enjoyed writing the character of Justin Scott, mostly because I despised him so much. You’re right, he’s very much an allegory for colonialism, and that was always the purpose I wanted his character to serve in this narrative. He’s a manipulative, dishonest, selfish, and skilled antagonist. A hardened survivalist, he presumes he can come into the community and be welcomed and take what he needs. These are all traits in direct opposition to the virtues of Anishinaabe life that the community members are trying to uphold. Physically, I wanted to paint him as distinctly from the rest of the characters as possible. I drew a bit of inspiration from the physical description of the character of The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. And I wanted to keep his background a bit mysterious, too. So I tried to draw up the kind of person I would not want to encounter in a crisis like this in my own home community. I both feared and loathed him throughout the whole writing process. 3. On that note, can you talk further about the Windigo, which you do a little in the note at the end? I’m glad you noticed that and brought it up, because the Windigo isn’t explicitly discussed in the story itself - only hinted at in a few subtle ways. It’s a figure in Anishinaabe and Cree stories that exploits communities at their weakest during the wintertime. There are many different stories about the Windigo with many different lessons and themes. As kids in our community, we learned that Windigo stories were told to warn people from cannibalizing one another and succumbing to evil and weakness in winter. Without giving too much away for people who have yet to read Moon of the Crusted Snow, some of these issues arise later in the book. And Evan eventually has a vision that hints at the Windigo’s presence in their community. Writing about this figure was important to me to pay homage to traditional Anishinaabe stories, as well as pay give a nod to my own family members and other renowned storytellers who shared these teachings with us. 4. A hallmark of dystopian fiction is the lack of answers--here, Evan doesn't seem to care what's happened to the world, only what's going to happen. I'd like to know what you think about that. I think that’s true. Evan’s outlook is what I believe sets this story apart from typical dystopian fiction. He’s looking ahead to how they can rebuild their community in this new era while bolstering their connection to the land around them. He’s well aware of his world around him, and although he doesn’t necessarily have the answers, he wants to work together with others to do things right for his people. When they find out the scope of the blackout after the two young men return from the city, he isn’t rattled. Instead, he looks inward and to those around him to figure out a plan. I admire that will, and would hope that I could respond in a similar way in such a crisis. At the same time, though, I didn’t want to put him on a pedestal as any kind of archetype. He’s an anti-hero in many ways. 5. Your first novel, Legacy, is also set on an Ontario reserve at a dark time. Do you see your vision changing with this book, or is it a development of what you began there? That’s a good question! I’ve never really considered drawing a line from one to the other. I think Legacy explores the tragic impacts of colonialism and the ongoing traumas endured by Anishinaabe people, and stays very present in those healing processes and conflicts. In some ways, Moon of the Crusted Snow is an extension of that, but it imagines a hopeful future and a community that sees a way to fulfil healing. I realize it’s kind of funny to call a post-apocalyptic story like that “hopeful," but it was important for me to illustrate what’s possible beyond the end of the world. So perhaps it is a development of that initial vision of understanding what communities endure as a result of being displaced and violated by the authorities. 6. The book's viewpoint shifts a little between Evan and Nicole. I sometimes get asked about writing from the male perspective. How did you find it to write Nicole’s? I’ve always found writing from the female perspective a little daunting just because I want to do those voices justice. But I believe it’s crucial to include those voices, especially when telling a story about my own culture and community. So I was inspired to write her by the many powerful Anishinaabe women I’ve known in my life. She’s by no means an amalgam of them, but she embodies many of the important things I’ve learned from them. I wanted to make her and Evan equal protagonists, although she’s not as present in the narrative as he is. But I think together, they reflect the virtues of Anishinaabe family and community, and they’re people I’d be honoured to know. Because she’s a strong leader on her own, I was a little more confident in exploring her as a character. 7. I think one of the book's underlying questions is, What is life for? (OK, not a small question!) Do you think it answers that? It may answer that question in different ways for different people. But for me the answer is pretty clear: life is for maintaining good relationships with each other and the land that nurtures us. 8. Do you have a few songs to go with this one? I sure do! I don’t listen to much music while writing, but I did listen to a handful of particular tunes when I wanted to get my head into writing, and to wind down afterwards. These are loosely related to some of the subject matter in the book: Nine Inch Nails - “The Day the World Went Away” Iron Maiden - “2 Minutes to Midnight” Propagandhi - “A Speculative Fiction” PJ Harvey - “The Ministry of Defence” A Tribe Called Red - “Burn Your Village to the Ground” You can find the book at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

1 Comment

5/3/2019 01:39:24 am

Sure this could be a good movie with those background music hehe

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed