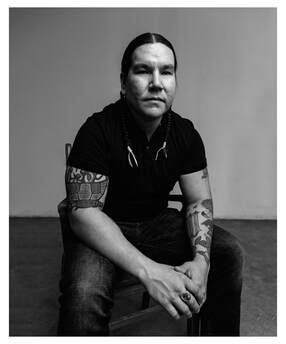

Mallory Tater's new novel, The Birth Yard, somehow feels exactly right for life in the coronaverse. It's set in claustrophobic confines, for one, where the outside world is made to feel extremely dangerous (and everyone wears the same clothes constantly . . . ). The cult known as The Den uses its female members for breeding. The women have been conditioned into contented acceptance, taking various drugs to control their fertility and moods. With her friends Dinah and Mamie, the book's protagonist, Sable Ursu, reaches breeding age, and the story follows her increasing unease during her "matching" with a man and subsequent pregnancy. Sable's slow movement from excitement to dull terror is one of this powerful novel's strongest feats (and I love Mallory's answer about teenage girls below). Mallory is also the author of the poetry collection This Will Be Good (Book*Hug Press 2018) and the publisher of Rahila’s Ghost Press, a poetry chapbook press. She lives in Vancouver with her husband and fellow writer, Curtis LeBlanc. I was happy she had some time to answer my questions --and that she got outside in this lovely dress for a photo! 1. Several generations of women in Sable’s family are present in the book, though her mother and Gram Evelyn are mainly in the background. We also see a little of Mamie’s mother and her difficulties. I’m interested in your ideas about lineage, especially for the novel’s women. I had a difficult time reconciling that, by the time the novel pivoted toward Part Two, there would be much less of Evelyn and Vale (Sable’s grandmother and mother). I tried to instill stories and tradition—kinship and ritual—between the women even though The Den discourages maternal relations of this kind. The moments in Part One where Sable, Evelyn and Vale sneak bread before dinner or chat about sexual intercourse or when Gram Evelyn shows Sable tarots, I hope, place those characters into Sable’s pocket to help her make the decisions she does at the Ceres Birth Yard in Part Two. Vale is much more traditional and obedient which kindles Sable’s kindness and sense of loyalty to her friends, while Evelyn’s rebelliousness, curiosity and slight devil-may-care attitude encourage Sable to channel her own thoughts and rhetoric into action when she is in the midst of injustices at her Birth Yard. Matrilineal lines inspire me greatly. When writing The Birth Yard, I had just undergone some family research of my own and travelled to Saskatchewan to learn about my great-great-great grandmother Elena Corches and my great-great grandmother, Rahila (her daughter). Rahila Corches (1888-1914), a young mother of three, immigrated from Campeni, Romania to Dysart, Saskatchewan with her husband, Samson, in hopes of finding stability, nourishment and safety. She helped her husband to build their sod house and maintain their emotional sense of home. She spent afternoons doing laundry and cooking with Canadian families in town to learn English. She died when she was twenty-six of unknown causes. In the St. George Romanian Orthodox Church in Dysart, Rahila Corches' death is listed as "extraordinary." Sable’s last name “Ursu” is actually named after my great-great Romanian Aunt Flossie who changed her maiden name Tater to Ursu. 2. “Natural” feminine qualities—domesticity, nurturing—are often part of real-life cults’ vision of how life should be. I like how the novel twists this idea. Can you talk about that? Basically, it was important for me to really lean into how Lynx and Feles [the cult leaders] and the ideology of The Den hold so much contradiction. Once the fear of their harsh punishments, sexist laws and false reverence are scraped away through Sable’s internal epiphanies and unlearning, it becomes clear, the men’s manipulations are out of their own fear of women, of being outsmarted by them. Feles isn’t super bright. He’s driven by narcissism and charisma. Narcissism and charisma can trick people into thinking someone knows best and someone is assertive and fair. It’s feigned intelligence. We’ve actually seen it in a raw, terrifying form in the US since November 2016 and it will only repeat itself so long as governments and work-forces are male-dominated. Well-known cults throughout history that have become household names, like Jonestown or the Branch Davidians or Children of God, hold this idea of bohemian, peaceful, utopic cooperation and use the ideas of nurturing, spirituality, selflessness and love to manipulate slave labour, physical, emotional and sexual abuse as well as totalitarian final say on all matters. Feles has done the same, but also has to silence women who may also hold those qualities because he doesn’t see them as equal and doesn’t want men’s roles threatened or diluted by women’s voices or opinions. 3. Writers like Megan Abbott have talked about the weird power of teenage girls, and the way they’re culturally feared. I wonder if this was on your mind as you wrote. I love this question. I have actually always felt that popular culture doesn’t take care of our teenagers, particularly girls, in a lot of mainstream narratives. We ridicule their intense feelings, often making them the brunt of the joke in television and movies with their hormones, changing bodies and mood swings. Teenagers are actually so beautiful in their intriguing balance of caring what the entire world thinks of them while feeling unhinged and brave as they discover their identities and values. They’re children one moment and autonomous budding adults the next. Sable, Dinah and Mamie represent that crossroads of naivety blossoming into true growth. There is power in unlearning internalized sexism and taking ownership of your own body through expression and defiance. And there is a lit flame in those teenage years to take back what is yours loudly and in numbers. It’s amazing. I miss my teenage self and my friends holding such intense space and being so focussed on ourselves and what made us happy. I definitely enjoyed creating Sable’s circle of friendships throughout the novel. 4. Although it’s sometimes easy to forget these characters are teenagers, you’re very good at intense teenage feelings! Because the world of the novel is so closed, and the perspective tightly inside Sable, I wonder how it felt to plot the story in emotional currents? Thank you for the compliment. I think the pacing of Sable’s unravelling from The Den’s value system had to hold a lot of patience in order for me to feel like I got it right. My editors also really helped me ensure she wasn’t too defiant from Chapter 1. It’s a slow burn and it entails scenes in which her worldview is disillusioned—slowly with elements of her father forcing her to demand a courtship with Ambrose up until she is later physically shamed and abused with a spitting ritual for breaking rules. Also, I tried to remember the newness of her experiences such as flirting with a boy for the first time, drinking alcohol, losing her virginity, standing up to her father and all the raw, fragile dialogue, body language and emotion that would come with that. I really enjoyed delving into the thought process of Sable's younger sister, Kassia, because she, at fourteen, sees her sister as sort of a deity and places her on a pedestal. This helped me understand the significance of all of Sable’s firsts, how they would be so poignant in her world and the world of her sister and friends. 5. Sable’s "Match" Ambrose seems gentler than some of the men, especially the group leaders. What does life in the cult does to its male members? Ambrose is definitely kinder and less threatened by his own ego than some of the men in the novel, but he also has inklings of toxic leadership and entitlement that trickle into his mindset. For example, he doesn’t really seek justice for Sable after the spitting ceremony and likes the special attention he receives from the leaders because of his father’s status. The nuances of inherited gender roles and their toxicity become so ingrained, and the organization and othering of women so normalized, that it’s hard for boys in The Den to grow into empathetic and kind men. If you are taught that your gender is superior your entire life, even if you do grow to love and have friendships with women, they’ll still hold this societal power imbalance. Ambrose may not be as abusive and cruel as his peer, Isaac, Mamie’s match, but he still embraces and sets goals for himself which honour the toxic masculinity of The Den. 6. This book manages to feel removed from this world, yet contemporary. What made you choose the present tense? Present tense keeps an active voice that creates a sense of agency and immediacy. It honestly energizes me to keep on with the narrative because every scene feels very pressing and tense. It helps me because I actually don’t plan my fiction. I write as I go without a lot of direction so the present tense seems to help give me more agency to move the plot forward and to stay focussed. 7. What do you think gives Sable the internal power to start questioning her situation? I think there are many elements that lead up to Sable’s epiphany that The Den and all she knows is actually quite dark and harmful and sour. But one moment that I personally feel matters a lot to her is the risk of Dinah’s pregnancy and how Sable realizes Dinah can easily be discriminated against if her secret is found out. Sable sees Dinah as someone who is rebellious with her cuss words and clothes, but not someone who is deserving of grave punishment. She can’t reconcile that Dinah could be so severely hurt. I think Sable’s removal from school, her own punishments for rule breaking and her discovery of how severe the drug treatments at her Birth Yard are lead her to question and to seek justice and freedom. You can pick up or order the novel from your local independent bookstore (like Mosaic Books here in BC), Indigo, or Amazon.

0 Comments

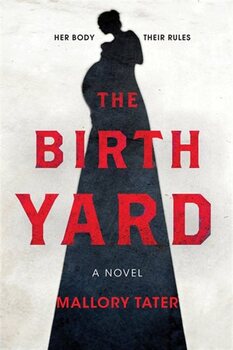

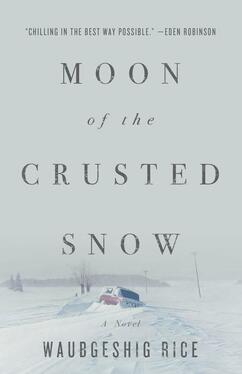

Photo credit: Rey Martin Photo credit: Rey Martin This fall, Waubgeshig Rice and I hung out in a lot of elevators at festival venues. It was always great to see his grin at various points on the road! We were both on the Cabaret bill at the Kingston Writers' Festival, where all the writers performed with live jazz backup, and Waub read from his newest novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow. Ontario CBC listeners get to hear Waub's voice all the time on Up North, but they don't often get to hear the show host read his fiction. He held the Kingston audience with the deceptively casual style of his reading--one of those sessions when you can feel the hook slowly pierce the room, and the entire group lets its breath out at the end. The quietly written, sharply outlined vision of life post-apocalypse depicts a northern First Nation family, Evan and Nicole and their two small children, trying to keep a community intact as things fall apart. I read it this winter, and though we're beyond the Anishinaabe late winter / early spring crusted snow moon now, the book hasn't let my mind go. Waub, a member of the Wasauksing First Nation, is a longtime journalist as well as a writer of short fiction and novels, and I'm glad to know he's working on a longer nonfiction project now. (Hurry up!) I'm grateful he had time to answer some questions about writing this book (and a little PJ Harvey on the soundtrack never goes amiss). 1. You're really good at quiet dread. I'd like to know how it felt to keep the tension up in writing this book, which is so much about everyday life in spite of some kind of disaster. Thank you, Alix! I’m glad you appreciated the building tension in the book. The story is more of a slow burn due to its rural and distant setting, so it was a challenge to keep that suspense building steadily throughout, even when there wasn’t much “happening”. A crisis due to a power and communications outage would unfold much more quickly in an urban setting, but this story takes place in a northern First Nation, where panic wouldn’t set in so soon due to the slower pace of life and the ability to adapt. And it was important for me to reflect that everyday life in this community, which is about close relationships with each other and the land, and less reliance on technology and infrastructure than in the city. Still, those luxuries have played an increasing role in the daily life of this First Nation, which is where that tension originally begins. Confusion arises around what prompted the blackout, if and when food and supplies will arrive from the south, and whether everything would come back online. Anyone who thinks long and hard enough about that kind of scenario would surely frighten themselves! So writing this story definitely became a tense exercise for me. I often asked myself what I’d do in that situation for my own family, and whether I’d actually be prepared for the end of the world as we know it. But in the end, I knew the resolution I wanted to come to with this story, and that kept me hopeful and at ease. The tension ultimately leads to another future, which is something that’s kind of exciting to consider. 2. Another part of the novel's structure is its representation of colonialism in miniature, with the white man Scott turning up looking for harbour. It would be easy to make Scott (whose name conjures up the British Antarctic explorer) a parody villain--just a one-note Bad Guy--but he's genuinely frightening because of how specifically you've drawn him. Can you tell me about writing him? I really enjoyed writing the character of Justin Scott, mostly because I despised him so much. You’re right, he’s very much an allegory for colonialism, and that was always the purpose I wanted his character to serve in this narrative. He’s a manipulative, dishonest, selfish, and skilled antagonist. A hardened survivalist, he presumes he can come into the community and be welcomed and take what he needs. These are all traits in direct opposition to the virtues of Anishinaabe life that the community members are trying to uphold. Physically, I wanted to paint him as distinctly from the rest of the characters as possible. I drew a bit of inspiration from the physical description of the character of The Judge in Cormac McCarthy’s Blood Meridian. And I wanted to keep his background a bit mysterious, too. So I tried to draw up the kind of person I would not want to encounter in a crisis like this in my own home community. I both feared and loathed him throughout the whole writing process. 3. On that note, can you talk further about the Windigo, which you do a little in the note at the end? I’m glad you noticed that and brought it up, because the Windigo isn’t explicitly discussed in the story itself - only hinted at in a few subtle ways. It’s a figure in Anishinaabe and Cree stories that exploits communities at their weakest during the wintertime. There are many different stories about the Windigo with many different lessons and themes. As kids in our community, we learned that Windigo stories were told to warn people from cannibalizing one another and succumbing to evil and weakness in winter. Without giving too much away for people who have yet to read Moon of the Crusted Snow, some of these issues arise later in the book. And Evan eventually has a vision that hints at the Windigo’s presence in their community. Writing about this figure was important to me to pay homage to traditional Anishinaabe stories, as well as pay give a nod to my own family members and other renowned storytellers who shared these teachings with us. 4. A hallmark of dystopian fiction is the lack of answers--here, Evan doesn't seem to care what's happened to the world, only what's going to happen. I'd like to know what you think about that. I think that’s true. Evan’s outlook is what I believe sets this story apart from typical dystopian fiction. He’s looking ahead to how they can rebuild their community in this new era while bolstering their connection to the land around them. He’s well aware of his world around him, and although he doesn’t necessarily have the answers, he wants to work together with others to do things right for his people. When they find out the scope of the blackout after the two young men return from the city, he isn’t rattled. Instead, he looks inward and to those around him to figure out a plan. I admire that will, and would hope that I could respond in a similar way in such a crisis. At the same time, though, I didn’t want to put him on a pedestal as any kind of archetype. He’s an anti-hero in many ways. 5. Your first novel, Legacy, is also set on an Ontario reserve at a dark time. Do you see your vision changing with this book, or is it a development of what you began there? That’s a good question! I’ve never really considered drawing a line from one to the other. I think Legacy explores the tragic impacts of colonialism and the ongoing traumas endured by Anishinaabe people, and stays very present in those healing processes and conflicts. In some ways, Moon of the Crusted Snow is an extension of that, but it imagines a hopeful future and a community that sees a way to fulfil healing. I realize it’s kind of funny to call a post-apocalyptic story like that “hopeful," but it was important for me to illustrate what’s possible beyond the end of the world. So perhaps it is a development of that initial vision of understanding what communities endure as a result of being displaced and violated by the authorities. 6. The book's viewpoint shifts a little between Evan and Nicole. I sometimes get asked about writing from the male perspective. How did you find it to write Nicole’s? I’ve always found writing from the female perspective a little daunting just because I want to do those voices justice. But I believe it’s crucial to include those voices, especially when telling a story about my own culture and community. So I was inspired to write her by the many powerful Anishinaabe women I’ve known in my life. She’s by no means an amalgam of them, but she embodies many of the important things I’ve learned from them. I wanted to make her and Evan equal protagonists, although she’s not as present in the narrative as he is. But I think together, they reflect the virtues of Anishinaabe family and community, and they’re people I’d be honoured to know. Because she’s a strong leader on her own, I was a little more confident in exploring her as a character. 7. I think one of the book's underlying questions is, What is life for? (OK, not a small question!) Do you think it answers that? It may answer that question in different ways for different people. But for me the answer is pretty clear: life is for maintaining good relationships with each other and the land that nurtures us. 8. Do you have a few songs to go with this one? I sure do! I don’t listen to much music while writing, but I did listen to a handful of particular tunes when I wanted to get my head into writing, and to wind down afterwards. These are loosely related to some of the subject matter in the book: Nine Inch Nails - “The Day the World Went Away” Iron Maiden - “2 Minutes to Midnight” Propagandhi - “A Speculative Fiction” PJ Harvey - “The Ministry of Defence” A Tribe Called Red - “Burn Your Village to the Ground” You can find the book at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

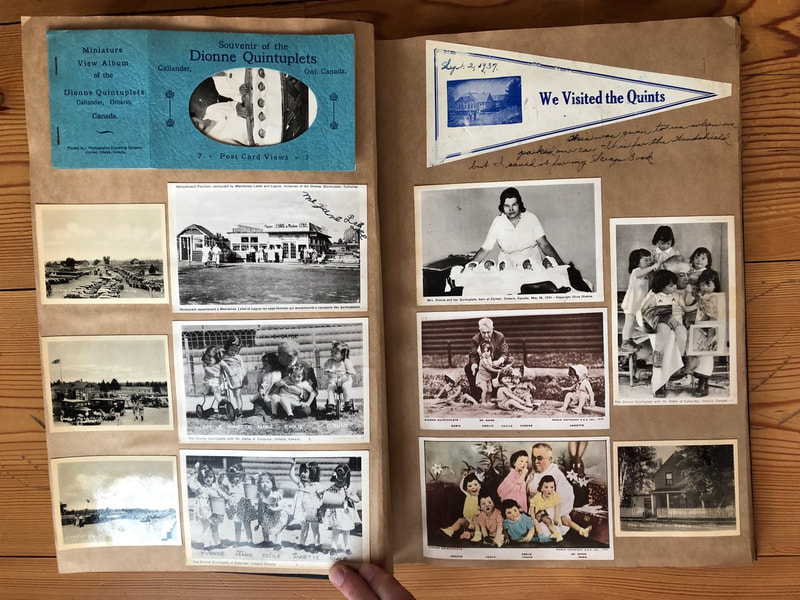

Like Clark Kent, Shelley Wood has cool glasses and secret superpowers. She's been a medical journalist for years, but has also more quietly been writing excellent short stories, and her first novel is out next week. The Quintland Sisters is about the so-famous-it-feels-like-a-movie birth of the identical Dionne quintuplets in rural Ontario in 1934. Partly in the form of a trainee midwife's diary, the book sinks into the five girls' earliest years and all the weirdness that surrounded them. It has a strong documentary feel, thanks to all Shelley's research (the Quints scrapbook above is part of her archival digging). She also has amazing ventriloquistic skills with her narrators--the main one, Emma Trimpany, is an invention, although I found myself Googling her just in case. Like I said, superpowers. Shelley is a fellow Okanagan resident, if a much more intrepid one than I am (she seems to be on top of Knox Mountain half the time, which may be why she has such a calm demeanour). When she was in drafting mode a couple of years ago, we bonded over our need to write a frame story that then has to be thrown out as you get towards what you really want to say. Shelley clearly got to the heart of what she wanted to with this beautifully written, sad, and thoughtful book. If you're in Kelowna, you can hear her read at her launch on March 5th. Other tour dates so far are here. 1. There's a quiet tension in the novel about world events of the 1930s. The narrator, Emma, blocks them out through her work nursing the quintuplets, sometimes almost obtusely. It made me think of Jane Austen being criticized for not writing more about war, etc., in her time; there's something a little Austenish about Emma (and not just her name). What's your view of her character? Oh, Emma. She thinks she knows everything, but is constantly bewildered when something unexpected happens. And perhaps like Austen’s Emma, she also sees the world she wants to see and convinces herself that she’s in the right. To me, she’s like most 17-year-old girls—self-possessed on the surface, but hopelessly unworldly. 2. The fascination with the Dionne Quintuplets has never gone away, although it's almost surprising to realize two of the women are actual people, still living. What's your sense of how this history became a myth so quickly? By 1934, when the babies were born, so many people had lost so much and their lives had become so hand-to-mouth, so dreary and desperate: they craved a real-world fairy-tale to lift them out of their day-to-day troubles. This was something the media, the government, and promoters of every stripe cottoned onto very quickly. I think the mythology around them was no accident; it was actively created by those who served to benefit. 3. Technical details! I'm so interested in the structure of this novel, which you set up as a file of documents--the overall diary, interspersed with newspaper articles and forms about the quintuplets, and finally a section of letters. Did you put it together in pieces? I explicitly set out to write an epistolary novel, made up of diary entries, letters, and other documents. It’s a format I love, not just because the reader gets to snoop through someone’s private papers, but also must work to fill in the gaps between the subjective and objective. Here, the letters and journal entries are fiction but the newspaper clippings, Blatz’s schedule, the Act for the Protection of the Dionne Quintuplets—these are all real, historic documents. And yet these are problematic too, the newspaper articles in particular, because far from being objective factual records, they were almost ludicrously biased, serving to continually stoke the public’s interest in this fairy-tale world. The timing of those final letters was also a choice. Most epistolary books that use letters to tell a story—think of Griffin and Sabine or The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society—provide both sides of the correspondence, chronologically. Instead, for most of The Quintland Sisters, the reader gets to see the letters that Emma has received, but they don’t get to read what she’s been writing in the letters she’s sending away. As a result, the letters at the end aren’t merely a replay, they are laced with all the prickling doubts that Emma couldn’t quite admit to herself, in her journals: they don’t tell quite the same story. 4. On that stylistic theme, I'm also curious about Emma's voice. Her diary feels removed from contemporary style, yet not "olde-timey," which isn't the easiest thing to do. How did it come to you? I wrestled, early on, with nailing a voice that was narrating events in the past tense, but always the very recent past—that day, that week—without the gloss of hindsight. Once I found that, Emma’s voice, which I wanted to have that diary-writer’s tone of confident self-consciousness, flowed pretty easily. 5. I can almost feel you pushing against expectations, especially in how the book deals with love. No spoilers, but I want to ask you whether that choice was deliberate. Absolutely! I knew almost from the start how I wanted the book to end for Emma, especially since the story of the quintuplets themselves continued on from here, tragically, and will likely never get a satisfying conclusion. The books I love most follow a pattern: they will always give you at least one thing that you’re desperately hoping for, but they won’t let you keep it. I aimed for that. 6. I like how you create a theme of birth and fertility beyond the quintuplets, straightforwardly and metaphorically. Can you talk about how you see that in the novel? Everyone who visited Quintland in the 1930s left with souvenir pebbles called Quint Stones that were supposed to bring good luck and fertility—as if those always go hand-in-hand. One of the themes I wanted to explore in this book was that of wanted and unwanted babies and, in tandem with that, wanted and unwanted motherhood. 7. The scientific and medical observation of the quintuplets is fantastically interesting as a document of the era. In your research, did you find any especially odd ideas about health or child-rearing (aside from corn syrup for babies!)? Dr. Allan R. Dafoe preached sunshine, cold air, and regular bowel movements, but he also signed up the quintuplets for endorsement deals for all sorts of health-giving products the girls likely never used or ate: Carnation Milk, Palmolive Soap, and Musterole Chest Rub, etc. But it was the child-rearing ideas of psychologist Dr. Blatz that I think were the most revolutionary for the day—he forbade spanking as punishment, but enforced a form of solitary confinement; he encouraged individualism, but discouraged the nurses from holding or soothing the girls. All these years later, Blatz’s books on the quintuplets are hard to stomach because he really did treat the girls as an experiment, where everything could be measured and tested and exposed to scientific inquiry. You can find The Quintland Sisters at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

Here's Emma Hooper, musician, novelist, knight. (Her musical project "Waitress for the Bees" has earned her a Finnish Cultural Knighthood.) She's also an expat Canadian living in Bath, UK, but I got to meet her on this side of the Atlantic at the 2015 Amazon First Novel Awards, where she read from her bestselling Etta and Otto and Russell and James. I was happy to see her (and her well-travelled baby) again last fall at the Vancouver Writers Festival. This time she pleased the crowd with part of her new book, Our Homesick Songs -- "a brilliant and tender dream," says Affinity Konar. It is that, but like Emma, and like its child characters, this book has a smart, slightly mischievous energy. Our Homesick Songs manages to be about the exodus of Newfoundland workers to Alberta, and also not quite fully of this world. It's filled with tiny perfections, like the pseudonym of "Don" for a teenage girl, who in turn names her wolflike dogs Giannina and Giancarlo. It folds in smaller stories, too, including one about how the snakes left Ireland, and the tales in old songs like The Water is Wide, which she talks about below. (Continuing the home-leaving theme, she'll be teaching a course in Italy this summer on Perfecting Your Prose. No envy here, none at all.) The image on the right is from Mark Clintberg's work, Not the one but there is no one else, which influenced Emma, and feels like a visual conjuring of her novel. (Clintberg is an artist friend of hers who made the piece in Newfoundland.) Watching Emma knit and manage all the book's nets is delightful. Here's what she had to say about writing and about being a semi-abandoned child of the '80s. 1. This novel is set in the 1970s and the 1990s, in Newfoundland and in the Alberta Oil Patch. So far, so grim, right? Yet this book is in no way grim, despite the economic anxieties and family problems it portrays. Can you describe your view of the tone? I think a simple way of describing it would be “hopeful.” The book is very much about a champion for hope, and hope for hope’s sake. The two child-protagonists, Cora and Finn, have very different plans and ideas, one quite gritty and realist, and one, well, not, but the hope they share is the same. It lots of ways the book is about looking back, to ancestry, cultural heritage, folklore . . . but it’s also about balancing that out by looking forward: to hope, the thing that pulls us forward. 2. I'm sure every interview asks you about music! Did you find musical structure influenced the novel's back-and-forth structure? And does any particular song go with this book for you? The folk songs in the book all have at least a bit of thematic significance individually, with The Water is Wide being perhaps the most potent. It’s a folk song so old and so scattered in lineage that you can’t actually trace it back to any one person or place, it’s a mosaic of a cultural artefact, passed down and pieced together by many different hands from different lands (I just made that up but it sounds like a saying, doesn’t it? Ha!). That’s an idea that important, central, even, to the book. As for musical structure, well, I do love to play with both white space and the back and forth of time and voice in a way that it’s likely my musical background underscores. It’s also, hopefully, a bit reminiscent of the inescapable sound of the wind and the waves in places like the outport community where Our Homesick Songs is set. A sort of melody-less song of itself. 3. On that note, I love the way the kids, Cora and Finn, are always practicing. The instruments are constants when their lives turn uncertain, but you're not sentimental about it. I'm especially interested in your portrayal of the tie between Finn and his accordion teacher. Can you talk about that? As a kid learning violin, my parents used to say I only had to practice on the days I ate. I wanted to represent this idea of a deep-rooted musical community, where making music isn’t a flashy or showy thing at all, no stages involved, just something natural that people do, that people have to do, that people have always done and will always do. 4. I kept thinking about parallel existences and other possible lives for these characters, which they think about too. How do you see that playing out in the settings--Big Running and Little Running, St John's and Alberta work camps-- which you describe quite differently? Anyone who has moved away from their hometown (or home country, even more so) knows the feeling of having to reassess what it is, exactly, that makes you you. The paired excitement of being able to be anyone or anything, being free from expectation and tradition, and, at the same time feeling somehow more bound by that tradition, that nostalgic idea of home, than ever before. I wanted to explore that liminal place in the book, especially with Cora, who, at 14, is also dealing with the overhauling of identity that comes with adolescence . . .. 5. This book walks the line between magical and realistic, and you stay just this side of magic. Can you discuss that a little? I think hope itself often walks this line, between magic and realism, and, at times, allowing ourselves hope can seem as fruitless or difficult as believing in magic, so it made sense for me to blend the lines between the two here, in this book. Also, much of the magical thinking and hoping comes from Finn, who, at 11, is in that in-between place himself, between the magical beliefs and ease of childhood and the realism of adulthood, so it made sense to me that his stories and plans should reflect that tension. 6. It's also about family history and different generations, like many novels, and there's certainly conflict, but to me, that's not the book's point, or its power. Does the title play into that, for you? Yep, certainly. The title, Our Homesick Songs, is a reference to an idea that comes up in the book, that ‘all songs are homesick songs’, meaning all songs—or music, really—has the power to transport us into our own past, in a Proustian Madeleine kind of way. Only I’ve extended that idea of person past to include our ancestral and cultural pasts too, songs, therefore, have to ability to connect us with our family and extended-community family over both space and time . . .. 7. Like you, I have young kids, and I'm envious of--or homesick for--these '70s and '90s parents who let their children go boating alone and wander around outside all day, etc.! Was that on your mind? Ha ha, yes! And '80s parents too, aka mine . . . I spent a crazy amount of time out exploring the woods and ravines around our house as a kid; it was amazing, of course, at least in retrospect. When I think of it as a parent it’s also terrifying, of course . . .. As for the characters in the book, well, I guess there’s a reason why most child-heroes are orphans, or at least semi-abandoned. The freedom gives them agency, as well as the time to hatch and follow-through ambitious, over-the-top, schemes and plans. You can buy the book at your local independent bookstore, Chapters, or Amazon.

The various faces of Dania Tomlinson! A fellow Canadian writer and mother (more on that in the interview), she was kind enough to be the opening act at the hometown launch for My Name is a Knife in September. And look at her beautiful novel, which Canadian Living named a top book of 2018. (On the right, it's looking all fancy in the store this week.)

Our Animal Hearts is her first novel. It has a deceptively pretty sheen. Beneath, it's a kind of excavation, a mystery / history of the Okanagan Valley (traditional territory of the Syilx / Okanagan people), and full of passionate writing and characters. Its turn-of-the-20th-century setting evokes how weird this place can feel beneath its own prettiness, and how weirdly and precariously the layers of its past sit on each other. The opening line is, "This lake has no bottom." The power of the wilderness is probably *the* Canadian Literature cliche, and I think Dania takes that on purposely. She has several fresh twists, including a monster that haunts people's dreams as well as the lake it has lived in for centuries. It floats in and out of the story's reality, and one of the things I love about this book is its overlaying of realities (not least the Indigenous and settler worlds), as I asked her about below. Gothic fans, this one is for you. But it's for psychological realism fans too. Maybe something like Alice Munro moving into Castle Rackrent. Dania grew up in the valley and earned her MFA at UBC. She's been writing for years; she worked on this book for ten. It's a little hard to reconcile her in-person joyful energy with the dark power of her novel. But that's one of my favourite dichotomies. 1. Your novel is set in the Okanagan Valley in BC, but also not--there's a half-real world that sometimes overlaps it pretty matter-of-factly. Can you tell me about how that works here? I think in terms of the "half-real world’" what I had in mind was more of an internal world--a world that is in fact very real, but just unseen. A personal, internal world, where our imaginings, our thoughts, our histories are made manifest. I was often asking myself: What if this fantasy/thought/fear was made physical? What would that look like? We all exist in our own version of reality, where are thoughts, memories, imaginings, are almost tangible. For example, in the Okanagan, the threat of a cougar following me through the forest is a very real possibility. And my imagination has always been a little obsessed with that. I picture this cougar following me. I can see it perfectly--velvet fur, yellow eyes. It disappears whenever I turn to look, but it is almost real. The fear of it though, is undeniable. 2. The epigraph is from the Welsh epic The Mabinogion, a work that's significant in the novel too. Do you remember when you first read it, and whether it influenced your structure or writing? I stumbled across The Mabinogion late in the editing process. I was well into my second or third draft with my editor and was researching Blodeuwedd, a man-made woman who is turned into an owl by her jealous husband. The Mabinogion is an English translation of ancient Welsh stories, many of which were first recorded in the Red Book of Hergest. Finding this text was like magic. As though someone in the 1300’s recorded these oral stories just for me. When I found water creatures in The Mabinogion, I nearly lost my mind. This text was a missing piece for Our Animal Hearts. Reading it gave me a fresh rush of energy for a story I had been writing and rewriting for nearly ten years. I’m not sure it really influenced the structure of Our Animal Hearts, although including The Mabinogion as a physical book in the novel allowed me to expand on a theme I was already interested in: storytelling, the stories we tell ourselves, the stories we tell others about ourselves, the stories that we remember, and most importantly, the stories that haunt us. I was already writing in parallel to this text without even knowing it. It was eerie. I still have goosebumps. 3. Speaking of the epigraph, it includes the lines, "There are no rude wants / With creatures." Animals, real and magically real, dead and alive, populate the book. How did that come about? Growing up so close to forests and lakes has made it impossible for me to imagine a world without animals. We see them everywhere and yet they exist in another realm; they’re like spirits. Animals are so unknowable, so beautiful, and so mysterious. And then there are animals that seem actually unreal to me, like peacocks. These birds are too ridiculous, too fabulous, to be real. Someone once used the word “animism” to describe the animal presence in Our Animal Hearts, but I don’t think that’s quite it. I like to tell a couple stories in response to questions about the animals. The first is about the cougar I already described. The second is that long before my grandmother died (the Welsh one) she said that after death she would come back as a blue heron. Now, since she’s died, my mom and I see blue herons everywhere. And it’s not that I really think my grandmother has come back as a blue heron (though, who knows!), but what matters is that when I see a blue heron I am mystified, and I think of her, and I am in wonder and awe. The bird has such weight that it has become a kind of symbol or saint to me. 4. The book is so much about various cultures bumping up against each other in one place: Indigenous, European, Japanese. What was it like to try to blend them? I think blending cultural stories more honestly portrays the human experience. We aren’t limited to only, for example, Biblical stories, or Welsh stories. In a globalized world, we come into contact with myths, legends, and fairy tales of various backgrounds; personal stories; histories; movies; songs; etc. etc. We are each influenced by limitless stories and often build up allusions and make connections willy-nilly. I like to use the term "mongrel stories" though I’m not sure that’s quite right. I think sharing stories and finding value and building connections between different cultural and personal stories might be a fruitful way forward in a world where there is often a lot of segregation and misunderstanding. 5. There's a lot about reading here, with many references to Iris's childhood reading, and to a private library, and to trying to learn words from other languages. I'm interested in your thoughts about that. This motif goes back to my obsession with storytelling. What stories influence us? How do we tell those stories? We always add our own personal slant when we tell a story. We absorb stories when we allow them in. We can’t help but alter them as they alter us. And then how are those stories communicated? Do they need to be told orally? What happens when they are written down? How does language limit our ability to share stories? Does a story lose meaning in a different language? What stories are inexpressible? What stories are only internal ones that we tell ourselves, that we have no language for? 6. Iris is the main character and the speaker, but her mother, Llewelyna, almost takes over the story, and maybe she's why you refer to the Welsh tale of Rhiannon eating her children. Can you talk about the push and pull between parents and children in the book? And maybe between siblings too? I like the connection that you made there. I find the Rhiannon story fascinating on many levels. It’s a story about storytelling, too! I am fascinated by motherhood, especially unwilling mothers or mothers whose personal lives are mysterious and disturbing to their children. Llewelyna is at the extreme end of the unwilling mother scale. That said, a mother’s love is often ferocious and not unlike hunger--not unlike a desire to devour. I love my daughter so much I could bite her. (But I don’t; promise.) 7. One of the lines that stays with me is, "Every few years someone disappears in the lake." Nightmares! Having grown up in the Okanagan too, I've always been obsessed with the lake and the monster and the stories about vanished bodies, and I wonder whether your own childhood thinking is in the book. My childhood is all over this book; it’s gone feral on these pages. My imagination was frantic as a kid, and to be honest it has lost little of its enthusiasm. I find that the story of the lake monster is rarely ever "told" to you, not in so many words. Instead, the lake monster has always already existed. It’s usually more something you learn when you overhear someone who is pointing out into the middle of the lake saying: “Look! There it is! It’s coming this way.”  That Tiny Life, Erin Frances Fisher's recent collection of five stories and a novella, is just so good (at left, Erin deservedly has it in the director's chair at a Toronto reading). I find the book's brilliance hard to categorize or analyze, as my questions below probably show, although it camped out in my head for weeks after I finished it. The stories have extremely varied settings and characters, but as Erin notes, they're all built around "hope and desperation." (Thanks to Erin for summarizing that, by the way.) My own answer is that these stories all feel mysterious but entirely complete, an unusual quality in contemporary fiction. Short fiction is my first love. I read a lot of it, and these pieces are standouts for their structure and voice as well as the breadth all the reviews mention. Erin's writing will run along evenly for a page, then you get the punch of startling, exact detail like "petals the size of fingers" or "Your small hips, the red compression lines from your corset." Erin's work has appeared in such journals as Granta and Little Fiction. She teaches at the Victoria Conservatory of Music here in BC. We'll both be at the Galiano Literary Festival next month, and I'm looking forward to hearing a reading in her own voice . 1. The blurbs for your book all mention the huge range of the stories, from Revolution-era France to a future on one of Saturn's moons. Did any of the settings come easier than the others? They were all interesting to write, but yes some settings were easier to find a way into than others. My family spent a few years in Inuvik, NWT, so I have some memories and stories from the north, and my sister is a falconer. The most time-consuming setting was revolutionary Paris. Although almost all Paris’s streets and museums are available virtually, the smaller details were difficult. Like when it rains, who would use an umbrella? And then, were umbrellas even invented? (The answer is yes, waxed parasols, and the wealthier merchant class.) I spent most of the summer in the university library reading through the history of harpsichords and fortepianos. 2. That Tiny Life is the Saturn story title. How did you decide it would be the collection title too? The title of the collection came before the title of the story, and it was actually my wonderful editor, Janie Yoon, who suggested we use it for both. Finding a title for the collection was difficult! Although there’s a thematic connection in the stories, they have very different narrators and settings. The collection needed a title that connected the stories, and “That Tiny Life” expressed the hope and desperation that the stories circle. 3. The White, a novella about a group of damaged people on a farm, is written in different third-person perspectives. The other stories all use first person. Can you talk about how the difference in voice felt to you? The White actually started out in first-person. I wrote a series of monologues in an attempt find a character to narrate, but I couldn’t narrow it down. The shifting point-of-view emphasized misunderstandings, and allowed for varying descriptions of setting, so I decided to keep all five narrators. I switched the point of view over to third person for smoother transitions, and because—after much revision—I found it worked better. Other stories in the collection started in different POVs as well: different narrators, or in third rather than first-person. 4. There's a sense of people trying very hard to reach each other, and not just in "Da Capo al Fine," where the narrator begins with "Cecile, I hope you'll hear what I'm saying." I'm interested in your ideas on connection in the stories. In “Da Capo al Fine” Tobias Schmidt addresses Cecile, repeatedly writing the same letter in order to explain. To me, he’s justifying his actions to himself as much as to Cecile—more even, as he hasn’t listened to her at all. Connection requires at least two people who are open to each other, otherwise it’s something else. So I suppose communication and miscommunication, willful misunderstanding—all that leads to situations that aren’t so great for characters, but are intriguing for the reader. 5. In another connection, animals are a huge part of the book, from a mule in the desert to sled dogs to breeders' falcons. Can you describe the human-animal link here? And what animals might represent? When I’m writing a story I don’t have a theme or symbol in mind, so the animals are firstly just animals. That said, in “That Tiny Life” the narrator’s grandmother breeds Golden Retrievers in a one-room apartment, and I admit choosing a breed that is the epitome of gentle dogs. Large, golden animals that seem friendly without reservation. An idealization of family for the narrator to look back on. 6. There's also money, and the lack of it--the haves and have-nots--a particular focus in "Argentavis Magnificens," where a pair of archaeologists get the funding of their dreams, with strings attached. I'd like to know your thoughts on how that contributes to the book's tension. Money is essential to everyone, and a necessary obstacle in life. Unless a character is in a money-free society then money will be a source of tension. The lack of it, or the overabundance, can cause all sorts of conflict. 7. I've been thinking a lot about music, knowing you're a pianist. The stories and novella all have their own structure, but do you feel that musical structure contributes to any of them? Yes and no? Yes, because music can be mapped the same way stories can be mapped, with rising tension and development through different keys and such. No, because I wouldn’t look at a specific musical structure and build a story around it. Another yes, because music is my job—I spend a lot of time teaching and working on pieces of music. The only intentional music reference is the title “Da Capo al Fine”, which in music means return to the start (literally da capo is “the head”) and play until the end. That story is structured as a letter Tobias Schmidt has written and rewritten many times. You can buy That Tiny Life via your local independent bookstore, Chapters.ca, or Amazon.ca.

I met Sofka at the Vancouver Writers Festival in October, where we were among the readers at the Afternoon Tea event (there she is at left on Granville Island, the venue, where even the weather cooperated). She read from her new novel, Putney, and the excerpt she gave in her beautiful voice gripped the room--a scene in which the 13-year-old Daphne is newly arrived in Greece with Ralph, her father's friend and secretly her "boyfriend." I picked up my copy immediately, and couldn't stop reading. Putney dives straight into the barbed wire of historical sexual abuse, how it's revealed, and how different genders and generations can react to it. The Guardian calls it "a Lolita for the age of #MeToo." With three narrative streams (Daphne's, Ralph's, and Daphne's friend Jane's), it slides easily between perspectives, a technical feat as well as a bold one. It's just been selected as an Observer Book of the Year, and is also a top pick in The New Statesman and The Spectator. Sofka's writing is elegant (as is she!). She's a journalist as well as a novelist, as the clarity of her prose shows. I was so pleased to speak with her about it. Putney is your title, with all the protagonists associate with that riverside London neighbourhood from their earlier lives. But Greece is a stronger force in the novel, in some ways. Did it symbolize anything for you in writing? Yes! I’d say this reflects something about my own life, as Greece has been such a strong force for me. I lived there as an anthropology research student and have been closely involved ever since. I eventually married a Greek and we have two bi-cultural daughters, who went to school in Greece. In Putney, I see Greece as symbolizing the place that Daphne is able to start anew and find a positive way of going forward after all her traumas. Putney is also the title of one of Daphne's fantastical fabric sculptures, which she comes to see very differently through the novel. You include a couple of passing moments of Ralph's thoughts on art by women, and his mindset seems to affect Daphne sometimes too. Can you talk about that? Ralph is very dismissive about what he sees as Daphne’s feminine work that uses fabrics (and other materials) for collages and hangings. He feels it’s not serious – drenched in estrogen! I suspect that some men are snobbish about “women’s work” or art that overlaps with craft. This was also an opportunity for the cultured, charismatic, successful Ralph to reveal himself as a snobbish bigot. I’m not sure whether his mindset affects the adult Daphne vis-à-vis her art, but she begins the books creating a sort of homage to her childhood and teen years and her love for Ralph. Later, she feels very differently, recognizing that she has honoured the man who abused her. The book is about age versus youth, adults versus children, but also specifically about hippie, arty Baby Boomers versus their children. One of the book's most devastating scenes includes Daphne's aged father's reaction to her telling him about her childhood abuse. I'm interested in that moment, and how she gets past it, and in your thoughts. -Daphne’s father has always loved his daughter, but he has also been neglectful. He didn’t notice when his friend was seducing his underage teenage daughter in the 1970s and he was too wrapped up in his work and his own affairs to pay attention. This egocentricity continues into old age, where he is unable to face up to Daphne’s suffering and her reassessment of what happened to her as child sexual abuse. Perhaps this is because he would have to reassess his entire life, so he is happier to look away and choose not to fully understand. It is his way of maintaining an equilibrium towards the end of his own life and perhaps reflects his fear that otherwise the fall-out could be devastating to him too. The shifting points of view give the novel its intensity. Did you know from the start you would write with three different viewpoints, all in third person? Did you try at all in first person? I always knew there would be two viewpoints of Daphne and her older lover Ralph, but Jane (as friend and witness) came in pretty early as an idea and I was quickly convinced of the book’s need for someone outside the heated [relationship]. I wondered about writing in the first person, but I was happier to keep a more unified narrative voice that comes with several characters having a close third person. More specifically, was it difficult to write from Ralph's point of view? I wonder what it was like to hear and express his way of thinking as you wrote. I found it almost worryingly easy to sit inside Ralph’s head! I’m afraid it’s because I’ve known several men who have certain characteristics of Ralph. His charm, deceptions and justifications just flowed. Jane is, to my mind, the most powerful character, and not just because of what she knows. I found myself alternately drawn in and repelled by her. Perhaps the negative reaction comes from her own feelings about her younger self, which you draw so strongly. Can you discuss your feelings about her? Jane is ostensibly the sensible, ethical character who calls out Ralph as the abuser he so clearly is, but that Daphne doesn’t initially recognize, even after decades. But ultimately, Jane is far from being a reliable narrator. One aspect of that is the envy she felt towards Daphne when they were young and the on-going insecurities about herself and her body, despite her success in her professional and family life. Another aspect is that she is not being entirely honest, even to herself, about her motives. Some readers are irritated by her, perhaps because of her dogged determination to persuade Daphne to go to the police and denounce the man she believed she loved all those decades earlier. Technical question: what was the first scene you drafted? Did it remain in the final version? I wrote several scenes before I started at the beginning. The first was when Ralph goes to Daphne’s house in the famously hot summer of 1976. He is collecting her so they can travel to Greece together on the hippy-ish Magic Bus – a trip that will end with them sleeping together for the first time. I wanted to bring out the extraordinary ability of young girls to veer between childhood and womanhood, so that there is something confusing to both the girl and the observer. It is this tendency that the adult Daphne later witnesses in her own daughter and that helps her to realize that a 13-year-old may play about with sexuality, but she is still a child. |

Storybrain

Alix interviews other writers about their work. Those listed in the Blog will be migrated here sometime! Archives

May 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed